Let’s avoid Christmas culture wars and be charitable

Fresno Bee, December 17, 2016

At recent rallies Donald Trump has announced, “We are going to start saying Merry Christmas again.” In Wisconsin, Trump spoke from behind a podium with the words “Merry Christmas USA” emblazoned on the front.

Meanwhile, the American Civil Liberties Union forced Knightstown, Ind., to remove a cross from the town Christmas tree. The Christmas culture wars are raging again.

Meanwhile, the American Civil Liberties Union forced Knightstown, Ind., to remove a cross from the town Christmas tree. The Christmas culture wars are raging again.

The Constitution provides some guidance. The First Amendment guarantees your right to say “Merry Christmas,” “Happy Hannukah,” or “Bah humbug.” You can plant a cross, a menorah, or a Festivus pole in your yard. However, the First Amendment prevents the government from imposing religion upon us.

But what about Christmas trees? The Indiana town removed the cross but left the tree. Christmas trees seem sufficiently secular to pass constitutional muster.

That tells us something about the meaning of “Merry Christmas.” The phrase can be a religious dog whistle. But it can also have a secular meaning.

Christians want to keep Christ in Christmas. For some, “Merry Christmas” is a proclamation affirming that Christ was born to save us from our sins. But most people are probably not thinking about theology when they offer a friendly “Merry Christmas.”

No yuletide greeting is entirely unproblematic. “Happy holidays” seems inclusive. But it leaves atheists out, since they don’t believe in “holy days.” “Season’s greetings” is more inclusive. But prickly pious types may take offense at such an insipid salutation.

Christ is certainly the root of “Christ-mas.” But what about the word “merry”? Even that word can be offensive since it contains a veiled hint about intoxication. The second-most-famous use of the word is in the phrase “eat, drink, and be merry,” where it points toward drunkenness.

Christmas parties are made merry with mulled wine and martinis. Some enjoy mimosas on Christmas morning. Christmas began as a drinking party. It developed from the Roman Saturnalia, a time of drunken merriment associated with the winter solstice.

Some Christians oppose gaiety. Christmas merriment was banned in England in the mid-17th century by Puritans under Oliver Cromwell. American Puritans such as Cotton Mather condemned the “mad mirth” of Christmas. For Puritans, salvation is serious business. Merriment in this world distracts us from the need to be saved from sin.

Can’t escape religious diversity

This brief history reminds us of religious diversity. Some view this world as a vale of tears. Others embrace the joys of life. We disagree about theology, the value of happiness and the meaning of life.

And that is why we need the First Amendment to the Constitution to guarantee religious liberty and prevent government from imposing religion upon us.

Religious diversity is a fact. According to the Pew Center, only 63 percent of Californians are Christian. Twenty-seven percent are not religiously affiliated. The remaining 10 percent include Buddhists, Hindus, Jews, Muslims, Shamanists, Sikhs and others.

Some non-Christians enjoy a secular version of Christmas. The Pew Center reports that 81 percent of non-Christians celebrate Christmas. Santa Claus, Christmas trees, and eggnog do not require faith in birth of a savior in Bethlehem.

Significant diversity exists even among Christians. Catholics and Protestants celebrate Christmas on Dec. 25. Orthodox churches celebrate it in January. Other Christians – Adventists, for example – believe Christmas celebrations are unbiblical.

Many roots to Christmas traditions

Christmas is not in the Bible, after all. The disciples did not commemorate Jesus’ birthday. Mistletoe, elves and reindeer were adopted from pagan sources, as was Santa Claus.

Christmas is also a product of pop culture. It includes Charlie Brown, Rudolph and Bing Crosby. We might note that Bing’s famous song “White Christmas” was penned by Irving Berlin, a Jewish composer. Berlin also wrote “God Bless America,” by the way.

It is a unique American blessing that we are free to say “Merry Christmas.” But we should use our freedom wisely. Liberty without compassion quickly becomes obnoxious.

Let’s be charitable with regard to religious phrases and symbols. It is rude to force a holiday greeting down someone else’s throat.

“Merry Christmas” is not a threat or a command. It is a toast to be said with a smile, not a sneer. It is an offering of hospitality, not an expression of hostility. In these dark winter months, we need less-malevolent mulishness and more making merry.

http://www.fresnobee.com/living/liv-columns-blogs/andrew-fiala/article121328108.html

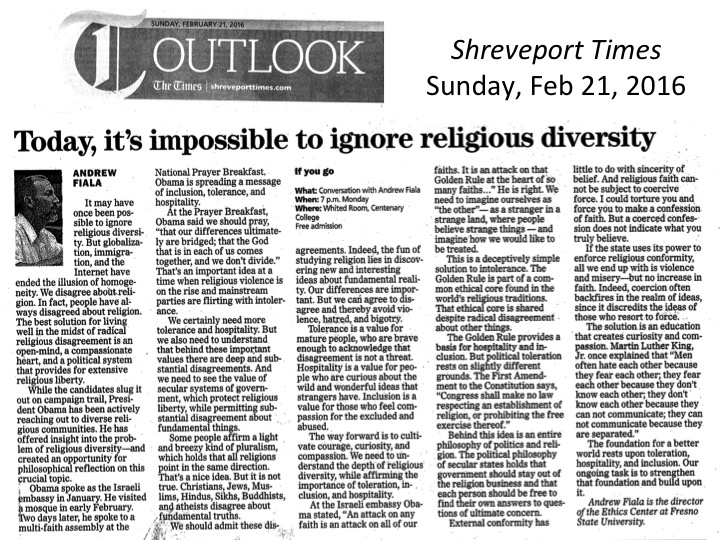

While the candidates slug it out on campaign trail, President Obama has been actively reaching out to diverse religious communities. He has offered insight into the problem of religious diversity—and created an opportunity for philosophical reflection on this crucial topic.

While the candidates slug it out on campaign trail, President Obama has been actively reaching out to diverse religious communities. He has offered insight into the problem of religious diversity—and created an opportunity for philosophical reflection on this crucial topic.