Fresno Bee , November 14, 2021

As local districts consider renaming schools, I suggest not naming them after people. Human beings are flawed. No one is perfect enough to have his or her name immortalized on a building.

Renaming is already underway in our region. Forkner Elementary in Fresno is being renamed for Roger Tartarian. The school’s original namesake was responsible for racial redlining that excluded Armenians, such as Tartarian. Meanwhile, people in the Central Unified School District are calling for Polk Elementary to be renamed. President James K. Polk was a slave owner who led U.S. expansionism during the Mexican-American war.

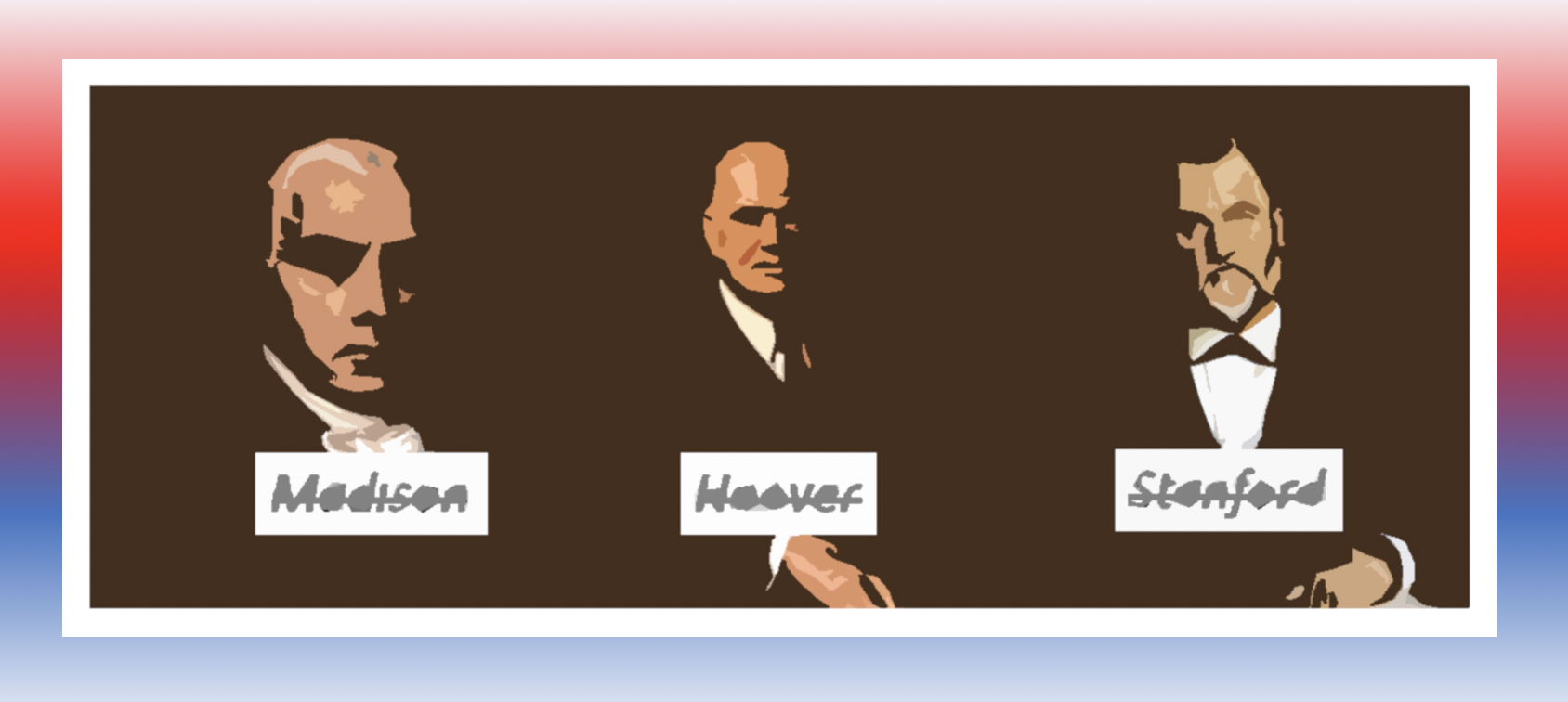

If you scratch the surface of many names, you’ll find problems. Herbert Hoover High School is named for a U.S. president who is typically blamed for the Great Depression. He has also been accused of racism. In 1932, W.E.B. Dubois said, “no one in our day has helped disenfranchisement and race hatred more than Herbert Hoover.”

At Stanford University there is an institute named after Hoover. The Stanford name is also controversial. Leland Stanford named the university after his dead son, Leland Stanford Jr. The elder Stanford was the governor of California — and a racist. In his inaugural address in 1862, Stanford said, “the settlement among us of an inferior race is to be discouraged, by every legitimate means. Asia, with her numberless millions, sends to our shores the dregs of her population.”

There may be some pure souls whose names deserve to be immortalized. But the naming process is often corrupted by wealth and power. It is the rich and powerful who put their names on buildings — or on entire universities. In America, we often confuse wealth and power with virtue.

Given this, it is strange that we continue to name buildings, universities, and even cities after people. Speaking of cities, the capitol of Wisconsin is named for James Madison, the father of the U.S. Constitution. But Madison was also an unrepentant slave owner. In Madison, Wisconsin today, they are trying to rename James Madison Memorial High School. Such are the ironies of American history.

One benevolent purpose in naming places after people is to memorialize role models. Role models are important. We learn through imitation. If you want to learn to play a sport or an instrument, you should imitate what good athletes and musicians do. But no human role model is perfect.

The case of Aaron Rodgers comes to mind. He is widely admired for his skill as quarterback. But his integrity and intelligence have been called into question due to his anti-vax views.

I’m disappointed, but not surprised by Rodger’s failure. Rodgers is good at throwing a football. Why did we expect him to make good decisions about medicine? We don’t expect doctors to be good quarterbacks. We each have our virtues — and our vices.

The same limitations hold true even of past presidents. They are skilled at politics. But it’s naïve to think they are flawless moral exemplars.

Each one of us is a creature of our own time. Past values influence the behavior of past icons. As our values evolve, former heroes fall from grace. This is inevitable. It is natural to reassess past heroes in light of current knowledge.

A further problem is polarization. In our polarized world, there are even disputes about the integrity of icons such as Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. We disagree about role models because we disagree about everything. Imagine the partisan outrage that would erupt if a school were to be named after Clinton, Bush, Obama, or Trump.

To avoid all of this, we might name schools after concepts — as I suggested in a previous column. This would be less polarizing. It would avoid the game of “gotcha” through which heroes are toppled.

I previously suggested naming schools after concepts such as “Liberty,” “Independence,” “Imagination,” and “Kindness.” We might also consider “Truth,” “Justice,” “Democracy,” “Fairness,” or “Responsibility.” How about Curiosity Elementary, Integrity Middle School, or Human Rights High School?

Finally, let’s include young people in these conversations. There is power in names and in naming. Students could be inspired and empowered by this opportunity. In doing the research and engaging the process, young folks can learn important lessons about history, democracy, and the power of names.