Masks are back, along with protests against them. Fresno County public health officials recommend that everyone wear masks again in public. This includes kids in schools, which prompted parents in Clovis to protest the need for kids to wear masks.

The resurgence of COVID is the vexing result of vaccine skepticism. Experts have explained that this is now a pandemic of the unvaccinated. This is frustrating for vaccinated people. We hoped the vaccine would get us back to normal. But that only works if everyone gets vaccinated.

Unvaccinated people are still supposed to wear masks. But anti-vaxxers are also likely to be anti-maskers. Unvaccinated and unmasked people are at risk. And it is through them that the virus spreads and mutates.

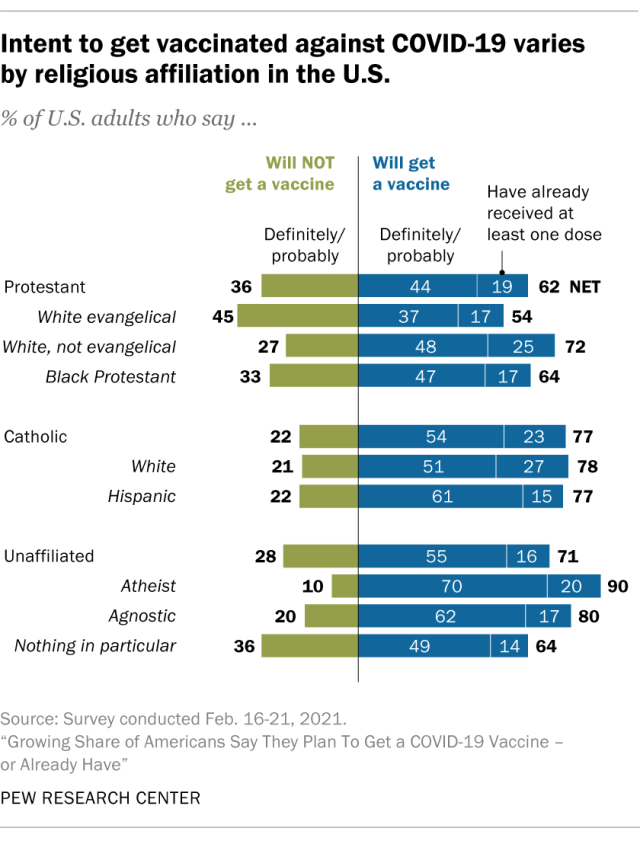

Political polarization is part of the problem. A report from the Kaiser Family Foundation shows that Republicans are less likely to get vaccinated than Democrats. But not every vaccine-skeptic is Republican. And some Republicans believe in vaccines and masks. Ignorance, fear, and selfishness are non-partisan problems.

Vaccine skepticism is more complicated than political ideology. Some religious people refuse vaccines on dogmatic grounds. Some people are allergic or have other health conditions that rule out vaccination. And vaccinations for children remain problematic.

This subtlety is ignored when people start casting blame upon the unmasked and unvaccinated. Some go so far as to invoke a kind of karmic comeuppance for the unvaccinated. I have heard more than one person say something like, “Well, it’s those unvaccinated folks own fault. They deserve what they get. I hope they hurry up and die so we can get back to normal.”

The people who say this usually say it with a wink and a whisper. They take it back quickly, claiming it is a joke or that they don’t really mean it. But it’s an awful thing to say.

This cringe-worthy blame game is a symptom of a profound social malfunction. The anti-vaxxers don’t trust the public health system. The pro-vaxxers don’t have any sympathy for the anti-vaxxers. As the pandemic continues, anger and exasperation are more common than kindness and compassion.

This dysfunction is similar to other rips in our unraveling social fabric.

Productive social life requires thick webs of cooperation. In a well-functioning society, cooperation is contagious. Successful cooperation makes people more cooperative. Cooperators are rewarded. As we share the goods of social life, we become even more cooperative.

But when cooperation breaks down, there is a vicious cycle fueled by distrust and animosity. This has been described by psychologists and philosophers in terms of “the prisoner’s dilemma” and “the tragedy of the commons.” The basic problem is that when we fail to cooperate, we end up with worse outcomes.

This helps explain a number of political and moral problems. Consider climate change. If other people are consuming mass quantities of fossil fuels, why should I cut back? As the climate heats up and the other guy is guzzling gas, I may lose the motivation to regulate my own consumption.

Or consider the controversy about the integrity of the 2020 election. If the other party is stealing elections or undermining confidence in democratic elections, then why should I cooperate? When trust erodes, democracy collapses.

Similar worries hold for COVID restrictions. Those who cooperated for the past year did so with the expectation that if everyone cooperated, things would get better. But the non-cooperators have undermined that hope.

This is a dangerous moment. We risk losing the buy-in of the folks who cooperated in the first place. Their virtuous behavior has not been rewarded. So, the motivation to cooperate fades.

One solution to this problem is moral. If the minor inconvenience of covering my mouth in public can save people’s lives, then I should mask up. Blame and karma ought to play no part in this moral calculation.

But moral concern is not the only thing that motivates us. Our emotions are also involved. That’s why we also need inspiration and hope. More people need to be inspired to get vaccinated. Those who wear masks need to be praised for their virtue. And those who are vaccinated need to be reassured that their cooperation was not in vain