Saturday is the International Day for Tolerance, which the United Nations has recognized since 1995. The United Nations explains that tolerance is “respect, acceptance, and appreciation” of diverse cultures and ways of life.

That’s a lovely idea. But tolerance is tricky. Do we have to tolerate intolerance? Can we censor those who express hateful and intolerant ideas? There are no easy answers here. And it is important to remember that censorship has often been used by churches and states to promote intolerance.

A guiding value for tolerance is liberty. To tolerate others is to leave them alone to pursue their own good in their own way. But harm provides a limit. If someone is harming you or violating your liberty, you need not tolerate them.

Is hateful speech harmful? That depends — on history, context, behavior, and intention. Hate is as complicated as love. And it does not exist in a vacuum. It is connected to anger, greed, impatience, violence and despair.

Nor does tolerance stand alone. It is connected to justice, courage, prudence, honesty and other virtues. These virtues ought to be woven together. But the goal of unifying the virtues is an aspiration that is difficult to achieve in our broken world.

Tolerance requires that we refrain from judging. But honesty requires that we speak our minds. Tolerance encourages us to leave others alone. But love compels us to intervene. And justice requires that we defend the innocent.

Genuine tolerance considers these complications and seeks a delicate balance. Intolerance operates differently. Intolerance simplifies. Intolerance reduces complexity to a binary choice between black and white.

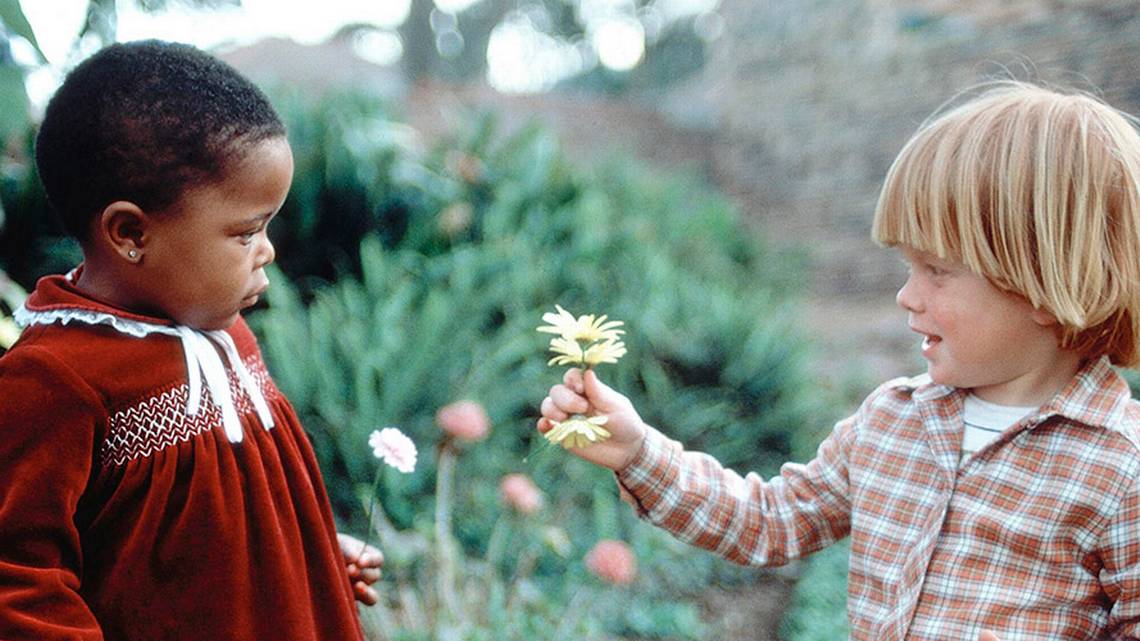

The palette of tolerance includes more colors. Tolerance grows when the imagination expands to see the depth of human diversity. Tolerance is taught through art, literature, history and philosophy. We learn tolerance when we study other languages, when we listen to new music, and when we read the poetry of other cultures.

Hellen Keller understood this. She said, “The highest result of education is tolerance.” She explained that genuine education “teaches us to unfold the natural sympathies of the heart.”

Those natural sympathies must be grounded upon a claim about human rights. Every human person has an equal right to respect. No person or group is inherently better (or worse) than any other. There is a kind of humility associated with tolerance that is quite different from the arrogant pride of racism and ethnocentrism.

Tolerance is also linked to curiosity and compassion. Tolerant people are interested in what other people think, believe, and experience. They put themselves in the place of the other. The Golden Rule of tolerance is to tolerate others as you would have them tolerate you.

Some 350 years ago, John Locke stated that toleration was “agreeable to the Gospel of Jesus Christ.” Intolerant religion demands external conformity. But Locke said that this was of no use in creating genuine religious belief. “All the life and power of true religion consist in the inward and full persuasion of the mind; and faith is not faith without believing.” Each person’s salvation is up to her. As Locke explained, “God will not save men against their will.”

Locke’s thinking had an impact on the American founders. The founders were not perfect. They tolerated slavery. But they also gave us the First Amendment. And Thomas Jefferson boldly stated that he would never “bow to the shrine of intolerance.” He rejected the arrogance of those who would exercise “tyranny over religious faith.”

During the intervening centuries, we have learned to be more tolerant of differences of religion, as well as sexual orientation, ability and race. We have also become more intolerant of racism, sexism and religious intolerance.

We are still figuring out where to draw the line. Some fuzzy issues remain, which require us to think carefully about all of our values. And this is the point: tolerance requires thought. The United Nations Declaration on Tolerance says, we teach tolerance by helping young people “develop capacities for independent judgment, critical thinking and ethical reasoning.”

Tolerance is a virtue of thinking people. We are not born knowing how to be tolerant. Rather, we learn tolerance as we expand our imaginations and understand the complexity of our common humanity.

While the candidates slug it out on campaign trail, President Obama has been actively reaching out to diverse religious communities. He has offered insight into the problem of religious diversity—and created an opportunity for philosophical reflection on this crucial topic.

While the candidates slug it out on campaign trail, President Obama has been actively reaching out to diverse religious communities. He has offered insight into the problem of religious diversity—and created an opportunity for philosophical reflection on this crucial topic.