What causes the powerful to come to ruin? In a word, pride

Fresno Bee, May 19, 2017

At a graduation speech this week at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, President Trump warned, “the more righteous your fight, the more the opposition that you will face.” He advised, “Don’t give in, don’t back down.”

That is standard fare for graduation speeches. Indeed, unrelenting self-assertion helped President Trump get elected. Persistence and tenacity are virtues. But the same disposition can become the vice of obstinacy.

Much depends upon the righteousness of your cause. But in general, obstinate self-assertion brings the powerful to ruin. At least, that is the lesson of the great tragedies. The drama unfolding in Washington could be written by Sophocles or Shakespeare.

Political tragedy is a microcosm, a fascinating display of the common human affliction. We see our own foibles reflected in the flaws of the powerful. The perennial lesson is that we are all subject to tyrannical moods. We push more than we yield. And we arrogantly cling to our own ignorance.

OBSTINATE SELF-ASSERTION BRINGS THE POWERFUL TO RUIN.

The tragic chorus reminds us that human power is uncanny and strange. Our power creates the conditions for our own downfall. The more powerful we appear, the more blind and lame we become.

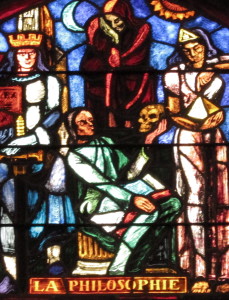

The problem is hubris, that fancy Greek word for arrogant pride. Hubris, the chorus explains, gives birth to tyrants. And tyrannical power begets hubris. Relentless pride, wanton ignorance, and unbridled ambition are the source of folly and crime. Shakespeare’s Macbeth warned, “vaulting ambition” overleaps itself. As the Bible put it, pride goeth before the fall.

Even a blind man can see that. In the Greek tragedies the blind prophet Tiresias makes the point. Everyone makes mistakes, he said. But good men yield when they are wrong. And they make amends.

The ancient tragedies also show that the cover-up is worse than the crime. A tyrant does not concede his failures. He never admits he is wrong. He lies and denies. And he blames the messenger for bad news.

The problem is power without restraint. As Lord Acton put it, “power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” One solution is a system of legal checks and balances. The law can prevent abuses of power. But virtue requires self-restraint.

It also helps to reflect upon the nature of power and ambition. Shakespeare provides a clue, suggesting in Hamlet that the substance of ambition is the shadow of a dream. Power inflames desire and our sense of entitlement. The more we get, the more we want. But political power is ephemeral. It is nothing but the opinion of others.

The game of power requires a constant effort to keep the hot air blowing in your own preferred direction. And when the winds shift, as they always do, the tyrant rants and howls like old King Lear raving on the heath.

Pride makes us stubborn and irrational. The young prince in Antigone warned his father against being inflexible and unreasonable. He suggested that his father should relent—and listen and learn. King Creon, of course, ignores this advice. The family is destroyed. And the desolate king learns too late the lesson of moderation.

IT IS IN MODESTY, DECENCY, HARD WORK AND CARING RELATIONSHIPS THAT HAPPINESS IS FOUND.

Tragedies also show that wisdom can be found in unexpected places—in the voices of the powerless. Throughout Western literature, powerful men routinely ignore and degrade women. They do not listen to the blind or the young. In Shakespeare, the fool offers insight. In Greek tragedy, it is the chorus of the people who provide the voice of conscience.

Here, then, is a source of hope. Normal people—lowly, hard-working, ordinary people—possess a kind of wisdom and virtue that the powerful seem to lack. We, the people, can learn from observing the tempests of political life a lesson of how not to live. We ought to discover that “wisdom is the supreme part of happiness” as Sophocles explains. It is in modesty, decency, hard work, and caring relationships that happiness is found.

The powerful fret and strut for their hour upon the stage—and then are heard no more. What’s left is a tale seemingly told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Those immortal lines are Shakespeare’s. His poetry has lingered, as have the works of Sophocles. And here is another source of hope. Empires rise and fall. But beauty and wisdom endure.

http://www.fresnobee.com/news/local/article151435597.html