It’s worth asking why Donald Trump remains popular. He’s been indicted for crimes including a scheme to subvert the 2020 election. A court ruled that he committed sexual assault. He paid off a porn star. His language and demeanor are divisive. If you want a soft and sympathetic character, don’t look to Trump. But if you like rebels, Trump is your man.

You would think that all of these accusations would disqualify Trump from the political stage. But the former president is so popular among Republicans that he didn’t bother to show up to the Republican debate this past week. As the underdogs searched for the limelight in Simi Valley, Trump’s shadow eclipsed the headlines.

This past week, a court ruled that Trump’s business was liable for massive fraud. Other headlines reported that Trump suggested that the outgoing chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Mark Miley, should be executed. The Wall Street Journal editorial board used words like “lunacy” and “unhinged” to describe Trump’s rants.

But people still love Trump. Republican voters appear to think that the indictments are unjustified political persecution. They see Trump as a martyr who is being attacked by a corrupt federal bureaucracy. From this standpoint, it is the cops, the courts, and the generals who are the bad guys.

If we push a bit deeper, we stumble upon a strange theme in American culture: the cult of the rebel. Americans idolize rebels and vigilantes, bad guys and martyrs. We tend to view those in authority as self-righteous hypocrites who abuse their power. And we cheer on those who throw mud at the stiffs in uniform.

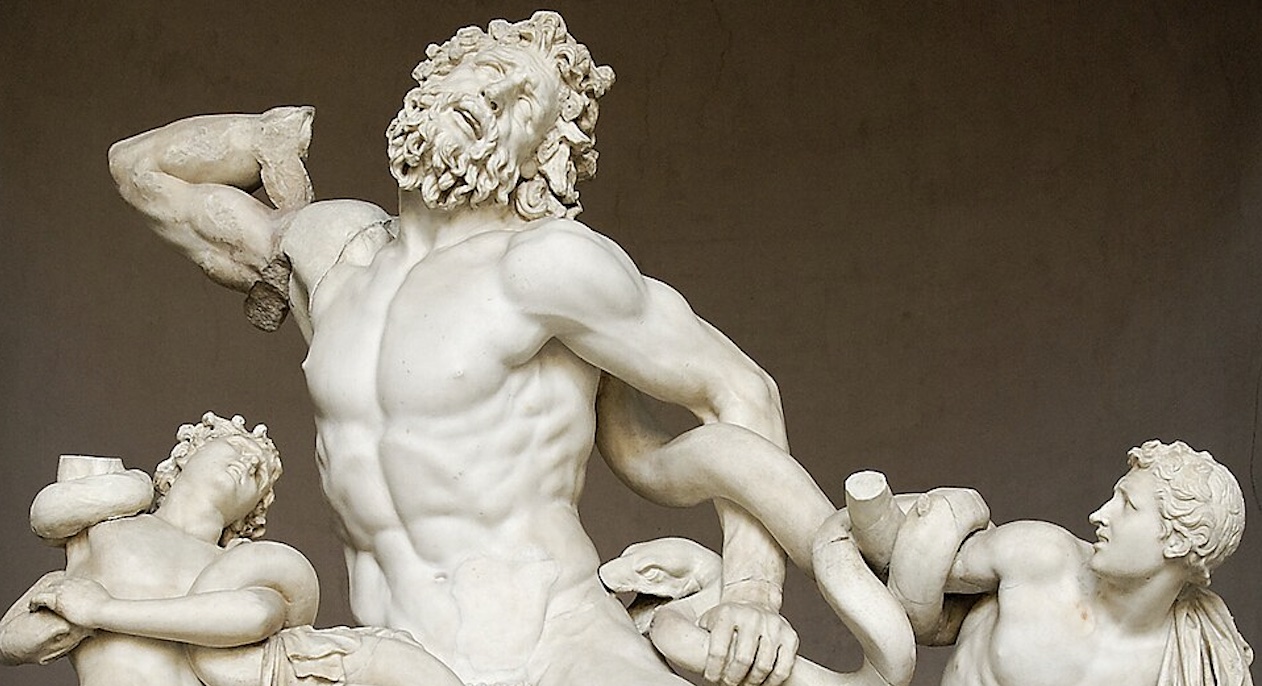

We might trace the cult of the rebel all the way back to Jesus and Socrates, rebel martyrs who questioned authority. But this is also uniquely American. The founding of the country was revolutionary. The founders heroically pledged their “sacred honor” to the rebellion of 1776. In 1787, Thomas Jefferson said, “a little rebellion now and then is a good thing.” He described rebellion as “a medicine necessary for the sound health of government.”

Rebels and outlaws are icons of American culture. Criminals like Billy the Kid and Al Capone are favorite fixtures of Americana. Pop culture often portrays bad guys and gangsters as heroic figures who have no choice but to use violence to defend their sacred honor. There is a whole genre of heroic vigilantes, including Batman and Spiderman.

The cult of the rebel implies that for good to be done, good guys have to go rogue and break the law. Instead of obedience and conformity, rebel culture values honor, pride and self-assertion. This is a bipartisan tendency. Leftists wear Che Guevara T-shirts, and right-wingers view the Jan. 6 rebels as patriotic heroes. Rebels on the left and the right think the establishment, the system, or “the swamp,” is made up of biased bureaucrats who are venal and corrupt.

This cult of the rebel is part of the dysfunctional attitude of what I have called elsewhere the moronic mob. The unthinking mob wants heroes and villains, spectacles and melodrama. It is fun to cheer on the rebels in “Star Wars” as they battle the empire. We rally with Neo as he fights the Matrix. And we sing along with the hippies, punk rockers, gangster rappers, and outlaw country stars who celebrate sticking it to the man.

This is all, of course, childish and dangerous. Rebellion is rarely justified and often unpredictable. Vigilantes end up in jail. Modern societies cannot function without widespread commitment to the rule of law. And most cops, lawyers, judges, and bureaucrats are decent folks trying to do their jobs.

But the story of decent people operating within the rule of law is boring. Reform is slow, incremental, and tedious. Rebels spice things up. And the mob is always hungry for what is spicy and spectacular. But ordinary social and political life is rarely spectacular or spicy.

Even if he outrages you, Trump isn’t boring. I personally think that boring would be nice for a change. But we are unlikely to be bored as the next presidential election unfolds. The cult of the rebel runs too deep. And we, the people, seem too fascinated by the spectacle to look away.

Read more at: https://www.fresnobee.com/opinion/readers-opinion/article279879484.html#storylink=cpy