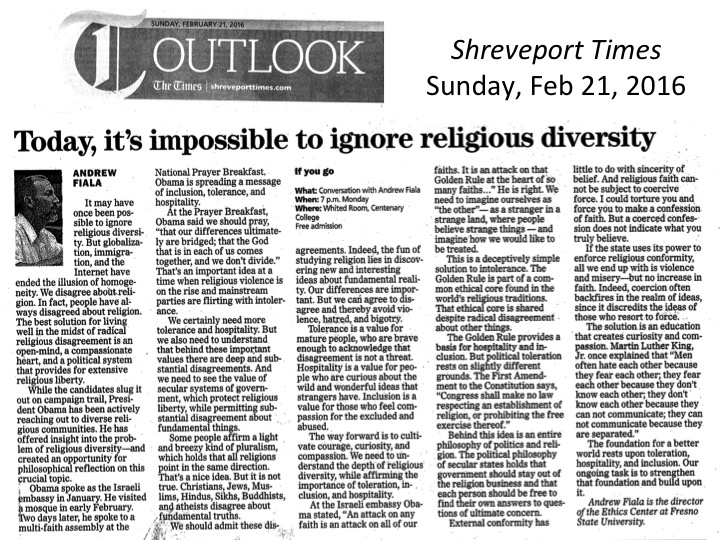

Today, It’s Impossible to Ignore Religious Diversity

Shreveport Times, Sunday Feb. 21, 2016

It may have once been possible to ignore religious diversity. But globalization, immigration, and the Internet have ended the illusion of homogeneity. We disagree about religion. In fact, people have always disagreed about religion. The best solution for living well in the midst of radical religious disagreement is an open-mind, a compassionate heart, and a political system that provides for extensive religious liberty.

While the candidates slug it out on campaign trail, President Obama has been actively reaching out to diverse religious communities. He has offered insight into the problem of religious diversity—and created an opportunity for philosophical reflection on this crucial topic.

While the candidates slug it out on campaign trail, President Obama has been actively reaching out to diverse religious communities. He has offered insight into the problem of religious diversity—and created an opportunity for philosophical reflection on this crucial topic.

Obama spoke as the Israeli embassy in January. He visited a mosque in early February. Two days later, he spoke to a multi-faith assembly at the National Prayer Breakfast. Obama is spreading a message of inclusion, tolerance, and hospitality.

At the Prayer Breakfast, Obama said we should pray, “that our differences ultimately are bridged; that the God that is in each of us comes together, and we don’t divide.” That’s an important idea at a time when religious violence is on the rise and mainstream parties are flirting with intolerance.

We certainly need more tolerance and hospitality. But we also need to understand that behind these important values there are deep and substantial disagreements. And we need to see the value of secular systems of government, which protect religious liberty, while permitting substantial disagreement about fundamental things.

Some people affirm a light and breezy kind of pluralism, which holds that all religions point in the same direction. That’s a nice idea. But it is not true. Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, and atheists disagree about fundamental truths.

We should admit these disagreements. Indeed, the fun of studying religion lies in discovering new and interesting ideas about fundamental reality. Our differences are important. But we can agree to disagree and thereby avoid violence, hatred, and bigotry.

Tolerance is a value for mature people, who are brave enough to acknowledge that disagreement is not a threat. Hospitality is a value for people who are curious about the wild and wonderful ideas that strangers have. Inclusion is a value for those who feel compassion for the excluded and abused.

The way forward is to cultivate courage, curiosity, and compassion. We need to understand the depth of religious diversity, while affirming the importance of toleration, inclusion, and hospitality.

At the Israeli embassy Obama stated, “An attack on any faith is an attack on all of our faiths. It is an attack on that Golden Rule at the heart of so many faiths…” He is right. We need to imagine ourselves as “the other”—as a stranger in a strange land, where people believe strange things—and imagine how we would like to be treated.

This is a deceptively simple solution to intolerance. The Golden Rule is part of a common ethical core found in the world’s religious traditions. That ethical core is shared despite radical disagreement about other things.

The Golden Rule provides a basis for hospitality and inclusion. But political toleration rests on slightly different grounds. The First Amendment to the Constitution says, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Behind this idea is an entire philosophy of politics and religion. The political philosophy of secular states holds that government should stay out of the religion business and that each person should be free to find their own answers to questions of ultimate concern. Related to this is a conception of religion, which holds that religion is something private and internal to persons.

External conformity has little to do with sincerity of belief. And religious faith cannot be subject to coercive force. I could torture you and force you to make a confession of faith. But a coerced confession does not indicate what you truly believe.

If the state uses its power to enforce religious conformity, all we end up with is violence and misery—but no increase in faith. Indeed, coercion often backfires in the realm of ideas, since it discredits the ideas of those who resort to force.

At the National Prayer Breakfast Obama pointed out that “fear does funny things.” Fear, he said, can lead us to lash out against people who are different. And it can erode the bonds of community. When we are fearful we resort to coercion. We want to destroy the thing we fear and we learn to hate.

The solution is an education that creates curiosity and compassion. Martin Luther King, Jr. once explained that “Men often hate each other because they fear each other; they fear each other because they don’t know each other; they don’t know each other because they can not communicate; they can not communicate because they are separated.”

King is right. The more you know, the less you hate. The foundation for a better world rests upon toleration, hospitality, and inclusion. Our ongoing task is to strengthen that foundation and build upon it—in our schools and institutions, and in our hearts and minds.