New poll shows 23% of Fresno County residents don’t affiliate with an organized religion

American religiosity is declining and diversifying. A recent Census of American Religion from the Public Religion Research Institute confirms a trend scholars have noted for decades. There is really no such thing as a typically American experience of religion. And lots of people have rejected organized religion.

This is what religious liberty looks like. In this country, you can change religions, marry someone from a different faith, or simply stop going to church. You can also openly criticize religion without fear of prosecution for blasphemy or apostasy.

Other countries lack this kind of liberty. When the State Department issued its annual report on religious liberty in May, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said, “Religious freedom, like every human right, is universal. All people, everywhere, are entitled to it no matter where they live, what they believe, or what they don’t believe.”

Blinken identified Iran, Burma, Russia, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and China as nations that harass religious minorities and punish religious dissenters. He accused China of committing genocide against its Muslim Uyghur minority.

American religious liberty is a rare and precious thing. But it is also messy and complicated. It means that we lack religious unanimity. It means that quacks can start cults. It means that some people will turn their backs on religion. It means that we all need to work harder to understand each other and the value of our freedom.

This is not good news for Christian nationalists who want the U.S. to be a Christian nation. Of course, the idea is problematic. Christianity is a big tent with substantial diversity. This includes many Christians who reject the idea of Christian nationalism.

A widely shared statement from “Christians Against Christian Nationalism” says that Christian nationalism distorts “both the Christian faith and America’s constitutional democracy.” They argue that Christian nationalism is idolatrous. And the First Amendment prohibits the establishment of any religion as the national religion.

Christianity is the identification of 70% of Americans, according to the PRRI Census. But Christianity is complex. It includes Protestants and Catholics, the Orthodox and the Mormons. The census also broke religious affiliation down by racial and ethnic lines, distinguishing, for example, between Black Protestantism, Hispanic Catholicism, and White Evangelical Christianity. One wonders how much there is in common between a white Mormon living in Utah, a Black Baptist living in Georgia, and a Hispanic Catholic living in Fresno.

Furthermore, nearly one in four Americans (23%) is not affiliated with an identifiable religion. Fresno County is typical in this regard with the same percentage of non-affiliated people (23%) as the rest of America. The Central Valley is generally more religious than the rest of California. In San Luis Obispo County, 36% are unaffiliated, for example. California is generally more diverse and less religious than the Midwest or the South.

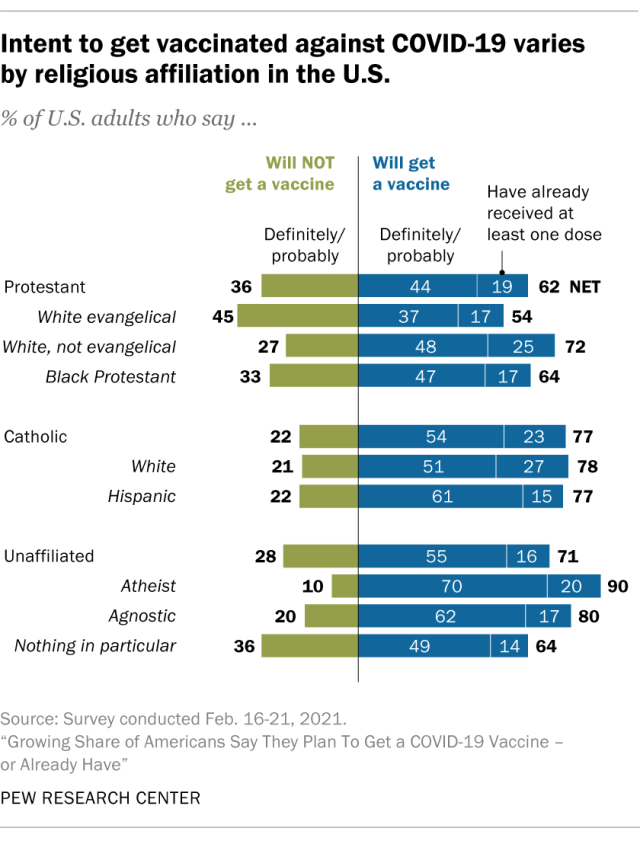

The unaffiliated are not necessarily atheists. Only 6% of Americans claim to be either atheist or agnostic. Unaffiliated people may be spiritual, but not religious. These folks believe in God or spirits, but are not members of any specific religious community.

One interesting data point is that there are as many atheists and agnostics as there are adherents of all non-Christian faiths combined. Jews, Muslims, and Buddhists each account for 1% of the population. Hindus came in at 0.5% (Sikhs were not accounted for separately).

This census confirms that this is a big country, where people are free to believe whatever they want. But religion cannot be ignored as a social force. There are regional differences. And religious differences track race, ethnicity, and political party affiliation.

This census implies that change will continue. Young Americans are more diverse than older generations. In the 18-29 age cohort, only 54% are Christian, 36% are unaffiliated, with non-Christians making up the rest.

This suggests an optimistic outlook for the future of religious liberty. Young people are exercising their liberty and creating a future that will contain more religious diversity than their grandparents encountered. Young people will need guidance as they re-weave the religious fabric of the nation. They need education about religious diversity and religious liberty. But the youth can also lead the way by showing the rest of us what freedom looks like.