Motherly love is neglected in ethics. The Golden Rule speaks of brotherly love. It says, “love your neighbor as yourself.” But we might also say: “love your neighbor as a mother loves her children.”

Brotherly love creates solidarity and respect. Motherly love is a more active process of nurture and care. A mother’s love is specific. It concerns itself with your unique well-being. Brotherly love spreads widely and grows thin. Motherly love is intense: it responds to your needs and encourages you to fulfill your potential. Brotherly love is universal and abstract. Motherly love is for real people with concrete needs.

Motherly love involves labor. To live well is to participate in the labor of mothering: to give birth, to nurture, and to care. We all do this. The poet is a mother. So too is the musician, scientist, and farmer. Anyone who gestates, nurtures, and grows things is a mother.

Patriarchal metaphors confuse us. We speak of founding fathers. We imagine an artist imposing his will on the world. We see the farmer as inserting his seed and extracting the fruit. But art, politics, and agriculture require nurturing care.

We also conceive of God as a father who begets a son. This patriarchal metaphor limits our imagination. Divine creativity is not masculine imposition. Rather, it is an unfolding from within. It makes sense to say that God gives birth to the world.

A hidden account of the importance of motherly love can be found in ancient philosophy.

When Pythagoras descended into a cave seeking wisdom, he was nurtured there by his mother. She was the only person he communicated with from his dark retreat. When he emerged from his cave, he began teaching about reincarnation. This symbolic re-birth—the emergence from a cave—shows up Plato’s allegory of the cave as well as in the Christian Easter story.

Pythagoras’s theory of reincarnation allowed that he had once been a woman. So it is no surprise that he brought women into his school. His wife, Theano, and his daughter, Damo, were among his most important disciples.

Socrates also spoke of mothering. He described himself as a midwife who helps others give birth to the wisdom that is within them. That process is guided by love, conceived in motherly terms.

The source of Socratic midwifery was a mystical woman named Diotima. She taught Socrates the mysteries of motherly love. Diotima said, “All of us are pregnant, Socrates, both in body and in soul, and, as soon as we come to a certain age, we naturally desire to give birth.”

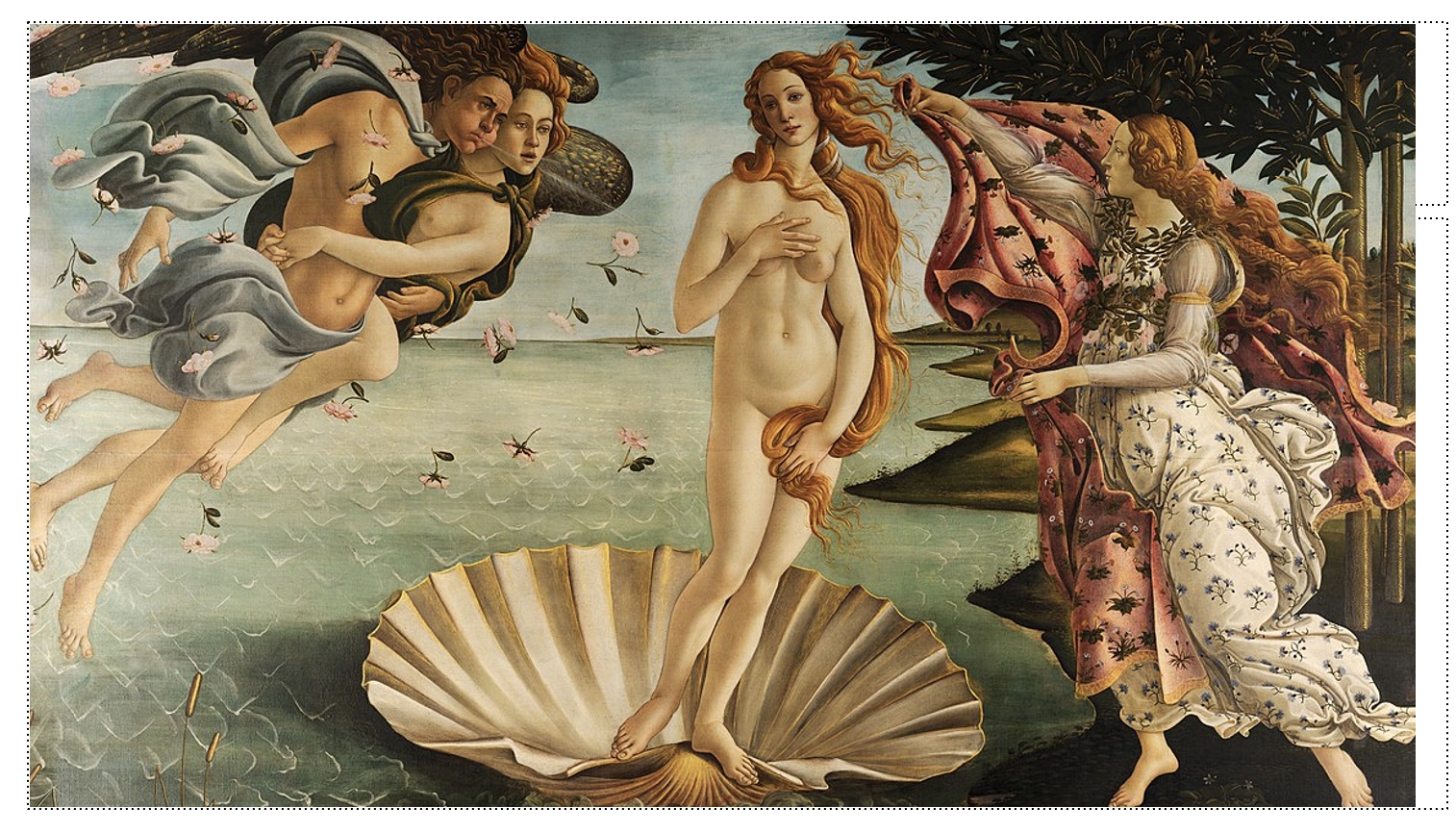

These ideas gestated and evolved for centuries until Plotinus offered a grand synthesis. He invoked female energies in his theology. The god of love, Eros, is the child of Aphrodite. Thus the creative energy of the universe comes from the goddess. And in one pregnant passage, Plotinus suggests that Aphrodite is identical with the cosmos itself, which is a process of the unfolding of motherly love.

These metaphors are fascinating. But we must be careful. In a patriarchal world, women are often reduced to their capacity to be mothers. A deeper vision of the power of motherly love calls patriarchy into question. The ancient thinkers hinted that mothering was fundamental. This vision empowered women as it did in the Pythagorean school. And it is inclusive: it is for women and men, poets and philosophers.

Contemporary authors have also made this point. Hannah Arendt focused on “natality” as “the capacity to begin something anew.” And Nel Noddings calls our attention to what she calls “the maternal factor.” Patriarchy ignores the amazing organic capacity of the female body. The life of the species flows through mother’s bodies. But motherly love is not merely about bodies: natality and maternity are spiritual metaphors.

Mothering is the compassionate heart of ethics. It is available to every human being who has been mothered and cared for. Brotherly love is fine. But a higher love models itself on a mother’s love for her children. This is a love that is careful, graceful, and nurturing. Motherly love is fundamental. It may even be the pregnant power of the universe itself.