Most Americans are ready to bury symbols of white supremacy. Let’s be done, already, with Confederate flags and rebel generals. Does anyone really care anymore about Braxton Bragg, Henry Lewis Benning, or Robert E. Lee, some of the Confederate generals whose names are fixed to American military bases?

But the president has resisted calls to purge these names. He said, “We must build upon our heritage, not tear it down.”

When someone uses a collective pronoun, it’s worth asking who is included and excluded. What counts as “our” heritage?

Is Robert E. Lee really one of “us”? He picked the wrong side and lost. How odd that we continue to immortalize him, 150 years after the fall of Dixie.

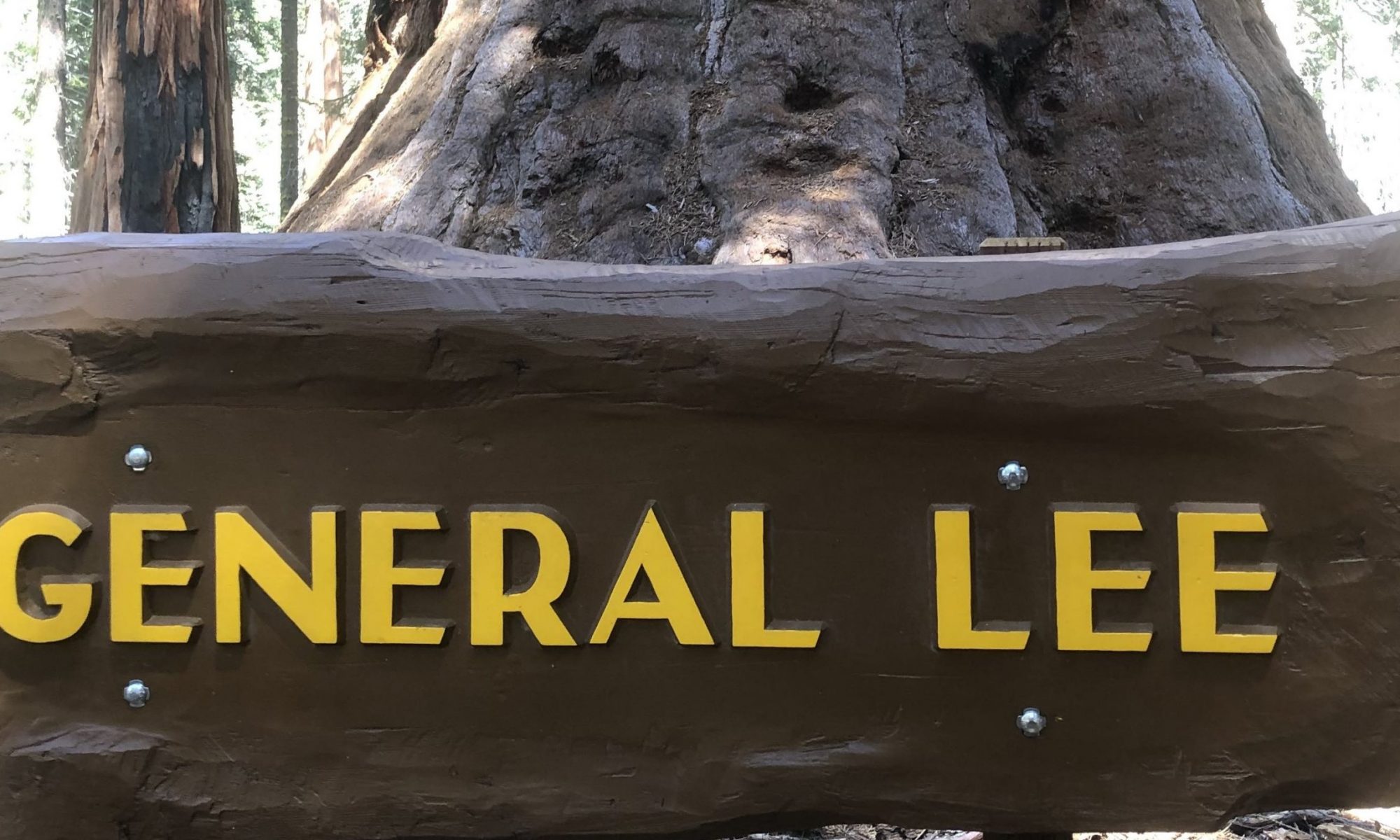

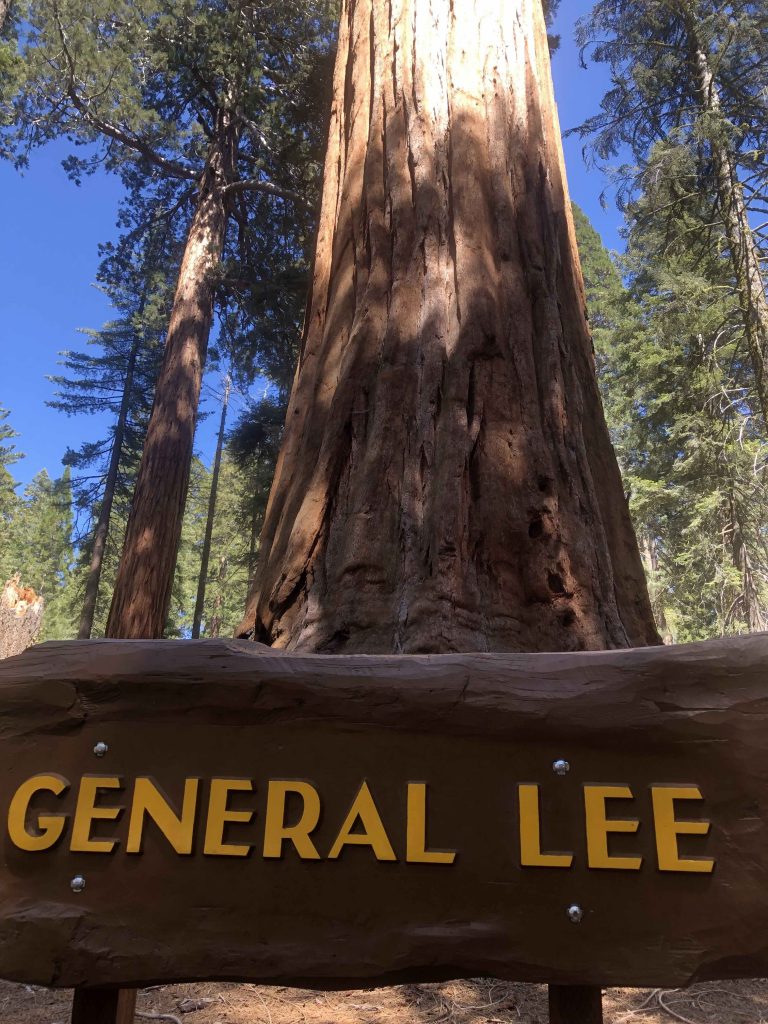

I thought about all of this while standing beneath two sequoia trees named for Robert E. Lee. The Robert E. Lee Tree is in Grant Grove up in Kings Canyon National Park. Down the road in Sequoia National Park stands the General Lee.

The General Lee is up the trail from the General Sherman Tree, the largest tree on Earth. The Sherman Tree is named for a victorious Union general. But this was not always its name. The utopian socialists of the Kaweah Colony originally called it Karl Marx.

The trees are indifferent to their names. They are thousands of years old. And unless we utterly destroy the ecosystem of the Sierra Nevada, these groves will endure long after the United States and its generals are forgotten.

The view from the sequoia groves is enlightening. These magnificent trees open a larger and more inclusive prospect. Our squabbles look absurd from the standpoint of millennia. The giant trees make racism and nationalism seem sadly short-sighted.

We are part of a system that exceeds the human imagination. Our true heritage includes the ancient sunlight trapped in the sequoia’s flesh. But the stories we tell remain narrow and cramped. And we seem incapable of telling the full tale of our heritage.

The U.S. is a nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the idea that all persons are created equal. But Native Americans were dispossessed. Slaves were only counted as three-fifths of a person. Mormons were driven out of American states. California was taken away from Mexico. And Marxists lived in the Sierra Nevada.

Our story is complex and evolving. But often the idea of “our heritage” is used to invoke a mystical idea about identity and belonging, blood and soil. This simply does not work in a diverse nation of immigrants, some of whom came here as slaves.

Many people are fascinated by heritage. They get genetic tests and trace out family lineage. I suppose this is fun. But the heritage game is not fun for everyone. Many hyphenated Americans — Irish-Americans, Japanese-Americans, or Mexican-Americans — trace their lineage back to those who chose to come here from “the old country.” This story is not so pleasant for African-Americans.

Perhaps it is time to be done with the idea of heritage. The historian David Lowenthal argued over 20 years ago that heritage is a dangerous idea. Heritage is not history. It is, rather, a mythical and politicized interpretation of the past. It is a fable that resists critical analysis. Lowenthal explained, “heritage exaggerates and omits, candidly invents and frankly forgets, and thrives on ignorance and error.”

A walk among the sequoia offers a cure. The vantage point of millennia teaches that life is fragile and diverse. The ancient trees remind us to embrace as much of life as we can, while we can. Nothing lasts forever. Not even these giants.

Nor do the sequoia know hatred, resentment, or intolerance. These trees do not belong to a party or a people. They have welcomed birds and butterflies for 2,000 years. This is a symbol of something inclusive, lasting, and strong.

And if the Robert E. Lee trees are ever renamed — perhaps after Martin Luther King Jr. and Cesar Chavez, as I might suggest — the trees themselves will remain indifferent. Heroes and nations come and go. The natural world is more substantial than any human heritage. And history is more interesting than the myths we tell ourselves about who we are and where we came from.