As the Respect for Marriage Act passed the Senate, the culture wars resurfaced. This law will guarantee that same-sex marriages and interracial marriages are respected. In response to the Senate vote, President Biden said, “love is love, and Americans should have the right to marry the person they love.”

I agree that this is good news for love. But didn’t we already resolve this issue? Well, the Supreme Court threw things into disarray with its Dobbs decision earlier this year, which called into question the idea of a “right to privacy.”

And while Biden praised the legislation, not everyone agreed. One commentator, R.R. Reno, editor of the conservative Christian magazine First Things, said that what he calls “the Rainbow Reich” was trying to radically restructure society. He said that the ruling elites are “determined to drive our country into a ditch.”

Albert Mohler, the president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, responded by saying that the Senate had “voted to redefine marriage, weaken society’s fundamental covenant, and threaten the religious freedom of Americans who, by religious conviction, cannot join in the legislation’s revolt against marriage and family.” He saw this legislation as a sign of “civilization crumbling.”

This hyperbolic language prompts a big sigh. When a civilization crumbles, you might expect marauding enemies. But letting people who love each other get married hardly seems to qualify as the end of civilization. This culture war re-run is a dud. It’s worth noting that 12 Republicans voted for the legislation. And those who opposed it seem like Scrooge at Christmas.

Biden himself was once opposed to gay marriage. He voted in favor of the Defense of Marriage Act in the 1990s. But society evolves and attitudes change.

Indeed, there is a growing acceptance of marriage equality. According a recent Pew Center survey, most Americans (61%) think it is good that same-sex marriage is legal. This opinion is more prevalent among the young: 75% of 18-to-29-year-olds are OK with same-sex marriage. For those over 65, that number drops to 50%.

The culture wars are getting old because they are being fought by older people. Young folks are ready to move on. And the warnings of the apocalypse fail to resonate.

But catastrophe is a handy rhetorical tool. Donald Trump is a practiced doomsayer. When he announced he was running for president again last month, he said that the Southern border had been “erased” and that the country was being “invaded.” He said, “The blood-soaked streets of our once great cities are cesspools of violent crimes.”

The merchants of doom hope to draw attention to the product they are selling by proclaiming that the end is nigh. In order for your party to save the world, the world must first need saving. Political and religious rhetoric are often infused with the rhythm and rhyme of doomsaying and messianism.

If you thought that things were going OK, why would you need a politician to save you? And if you were content with life and unafraid of death, what appeal would there be in religion?

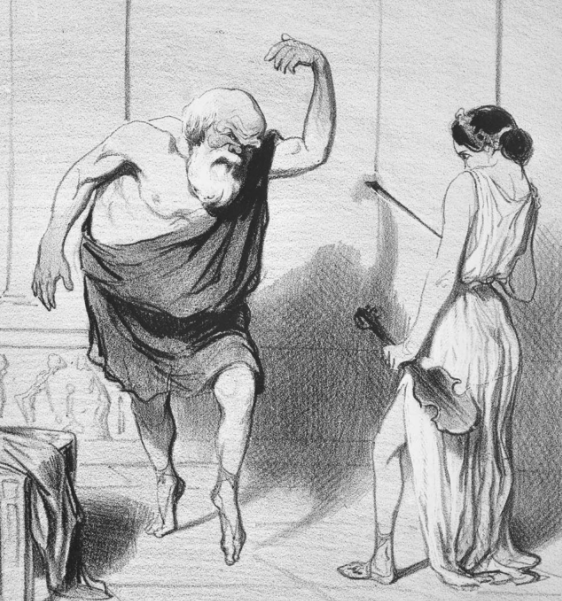

The idea that life is pretty good and that there is nothing to fear in death can be traced back to the teachings of the Greek philosopher Epicurus. The followers of Epicurus believed that happiness was easily obtained. They advised people to stay out of politics. And they basically ignored religion. The problem is that politicians and religious zealots have a knack for making us feel bad. A modern Epicurean might add that today’s media can add to our anxiety by amplifying the prophets of doom.

Epicureanism teaches us to stop listening to the prophets of doom. We should focus on easily obtained pleasures. We should mind our own business and leave other people alone to love and live as they want. It’s not true that civilization is crumbling.

Secular systems make life better for everyone because they allow us to enjoy the freedom to live how we want. Things are better today than in former years, when interracial marriage was illegal and when gay people lived in the closet. And if the doomsayers keep preaching about the decline of civilization, they may soon find themselves talking to empty churches.

Read more at: https://www.fresnobee.com/opinion/readers-opinion/article269497617.html#storylink=cpy