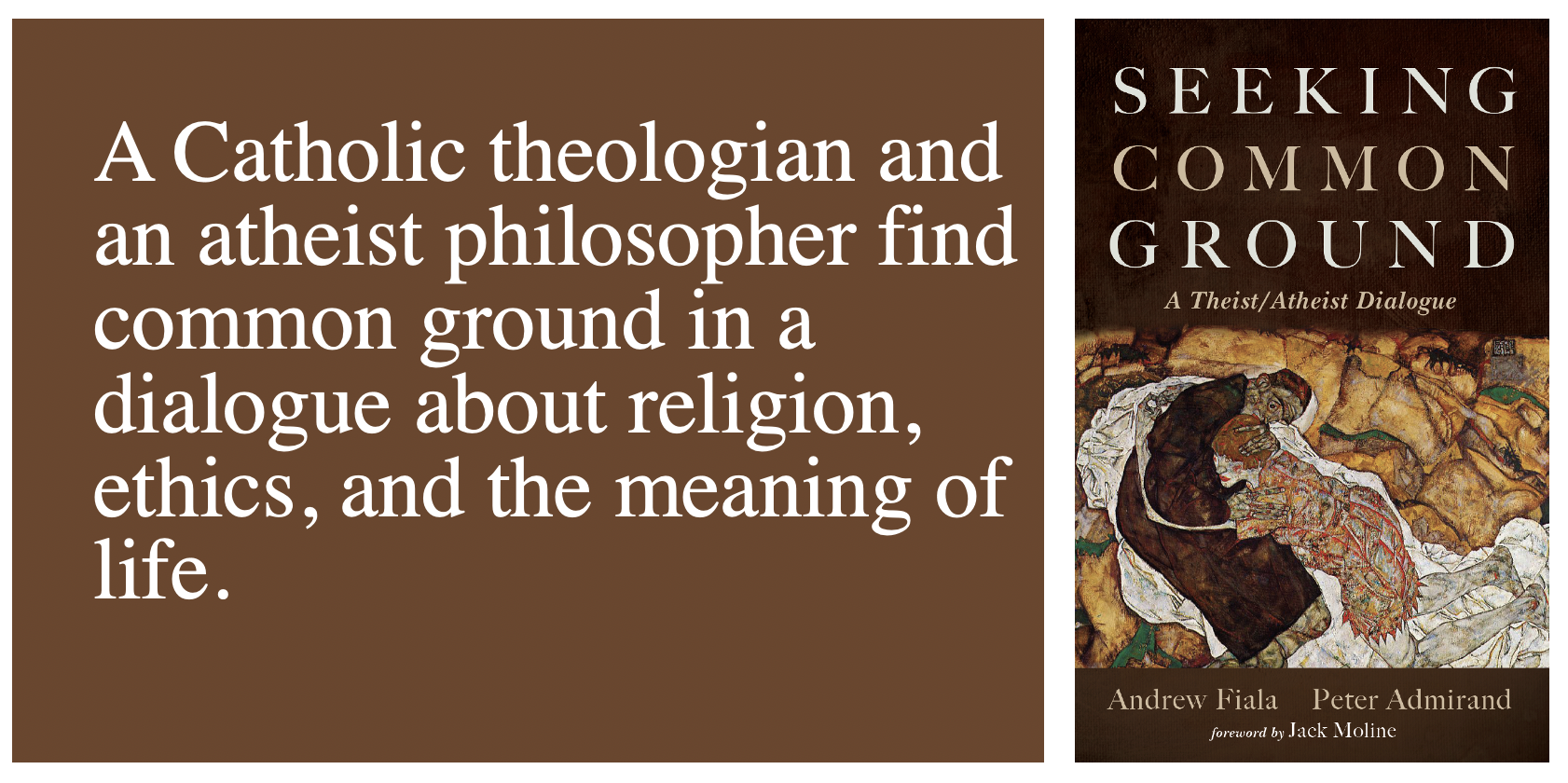

I’m pleased to announce the publication of a new book , Seeking Common Ground: A Theist/Atheist Dialogue, that I’ve co-authored with Peter Admirand, a Catholic theologian at Dublin City University. We worked together to think about our differences and what we share in common.

I’m an atheist. Peter is a believer. We disagree about some important and fundamental things. But we share the belief that dialogue and mutual understanding are crucially important in our polarized and divided world.

The book is framed by seven virtues of dialogue: curiosity, compassion, and courage, as well as honesty, honoring our commitments, humility, and the desire for harmony. If more people exercised these virtues the world might be a better place. The goal is not to erase our differences but, rather, to journey together to find common ground.

The book includes some biographical tidbits. I share the story of how I came to realize that I am more humanist than theist, a nonbeliever who remains interested in all of the world’s religions. As I explain, this was not a spectacular conversion from theism to atheism. Rather, it was a slow realization that the religion I was raised with no longer spoke to me.

Peter, of course, tells a different story. Our differences emerge in chapters that discuss the meaning of curiosity, compassion, and courage, as well honesty, humility, honor, and harmony. It was eye-opening to engage in this process with Peter.

The book ends with an account of letters (well, emails) we exchanged. We discovered a common love of music, a common love of friends and families, and a common concern about the crises emerging around us.

As I say, in the conclusion, I think we succeeded in finding common ground. But this does not mean that the conversation is over. Rather, there is alway more to be learned.

We were fortunate to have Rabbi Jack Moline, the President of the American Interfaith Alliance write a Foreword to the book. Peter and I are both engaged in interfaith and inter-religious work. We both think that this work needs to involve atheists, secularists, and humanists as well as members of the world’s diverse faith communities.

You can buy the book on Amazon or from Wipf and Stock Books.