Sloppy language is a sign of sloppy thinking. Our culture is brimming with slop. Prose piles up. Text scrolls by. Much of this is unedited and unenlightening. We are awash in words. But we are not any wiser.

Good writing and good thinking are undermined by procrastination and lack of focus. I see this in my students’ work. The later the submission, the more likely the typos. This is a distracted age. Hyperlinks open the floodgates of diversion. These flowing tangents impede concentration.

Students can be forgiven for their sloppiness. They are still learning how to think and write. But in the professional world, there is no excuse. We expect precision of language in scientists, doctors, lawyers and political leaders. This expectation of precision helps explain why the typos in Donald Trump’s response to the recent articles of impeachment have been widely mocked.

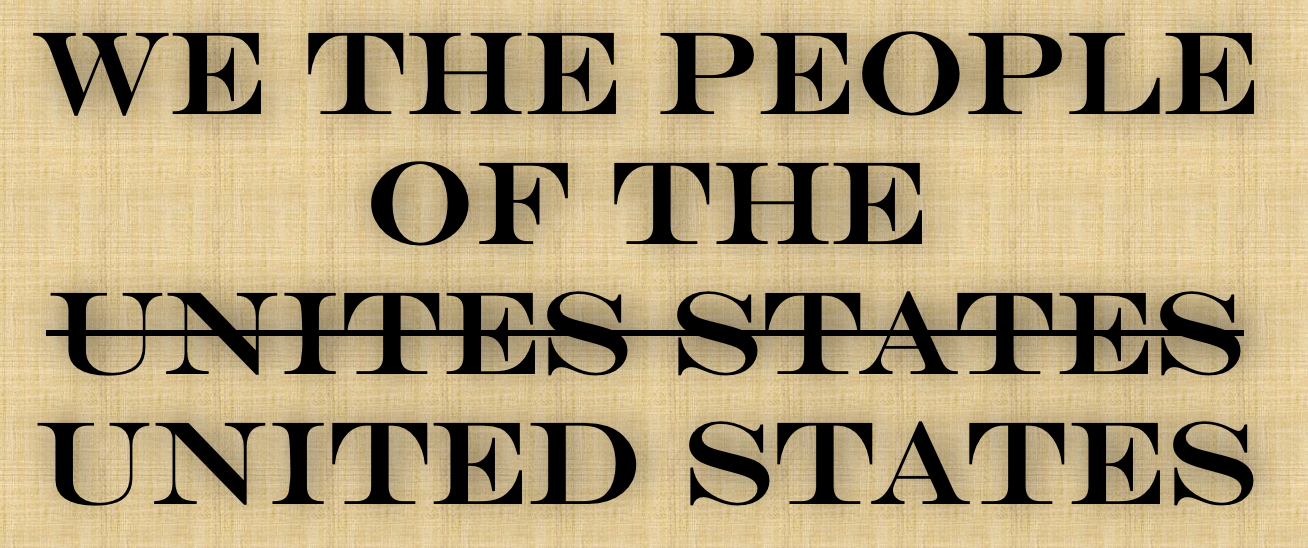

The former president is charged by the House of Representatives with inciting an insurrection. The gravity of this charge is profound. It requires a careful rebuttal. But on the first page of their response, Trump’s lawyers misspell the name of our country. The address line of the memo says “To: The Honorable, the Members of the Unites States Senate.” The same gaffe is repeated on page nine.

This typo is easy to understand. The “s” key is next to the “d” key. “Unites” is a word. So spell-checking software won’t flag it. Proofreaders often overlook titles and italicized words. We also know that Trump struggled to find attorneys willing to defend him. It is easy to imagine these last-minute lawyers frantically typing in the wee hours.

These kinds of mistakes happen when we are rushed or stressed. We’ve all been there. A deadline looms. You work hard to meet it. You hit send. Only later do you notice your linguistic blunders.

Often this is no big deal. The importance of spelling and grammar depends on the context. An occasional “covfefe” in a tweet only makes us human.

But there are moments when the text needs to be perfect. A typo in your resume can lose you the job. Grammatical ambiguity in contracts and laws cause legal battles.

Some documents have profound historical and legal import. Scholars quibble over commas and word choice in ancient religious texts. Disputes about the Constitution concentrate on textual subtleties. This linguistic quibbling is part of the current Trump impeachment.

The question about whether a former president can be impeached depends upon how you read the word “and” in the Constitution’s description of impeachment. The Constitution states, “Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States.”

Does this mean, as Trump’s defenders argue, that impeachment is no longer valid once the office holder’s term is completed? Trump’s attorneys say that removal from office is “a condition precedent which must occur before, and jointly with” disqualification.

On the other hand, the brief against Trump claims that the placement of the word “and” suggests that impeachment can also extend to disqualification from future office. The House impeachment managers argue, “The Framers then provided two separate remedies, both focused on an offender’s ability to seek and exercise government power: removal from office and disqualification from future officeholding.”

In the impeachment trial, in addition to this technicality of constitutional interpretation, we will see lots of discussion of Trump’s language. Words like “incitement” and “insurrection” will be debated, along with the general sloppiness of Trump’s language and thought. A significant question will be whether Trump actually meant what he said when he incited the crowd to riot.

The takeaway for ordinary people is to be more careful in speech and thought. Clear thinking depends on clarity of expression. This is especially important in formal communication. Technicalities matter in professional life. Typos can destroy careers. Laziness can lead to liability. And loose language can start a riot.

Wisdom is not measured by the volume or velocity of our words. Good thinking takes time. Good writing requires revision. If you want to be understood and respected, you must slow down and choose your words wisely.