A virus spreads. The stock market tumbles. Store shelves clear. People are freaking out. The best advice for times like this is: don’t panic.

Panic undermines clear thinking and makes things worse. Luckily, the cure is well known. Get the facts. Seek a broader perspective. Focus on what is under your own control. Develop habits of calmness and self-control. And acknowledge that sickness and death are part of life.

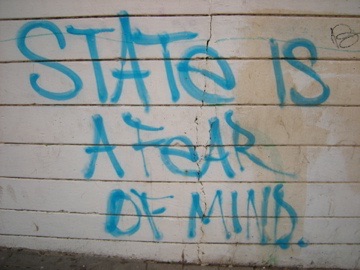

The word “panic” comes from the name of the Greek god Pan, a feral god who haunted the wild places. Pan was the god of the nightmare and the uncanny. Pan would terrify and possess people, causing panic.

One solution is to stop believing in such superstitions. The wilderness is not haunted. Gods cannot possess us. Nor is the coronavirus sign of the Apocalypse, as some preachers have suggested. And while some Christians called for a global day of prayer to stop the coronavirus, what we really need is a vaccine, better hygiene, and a robust system of public health.

The ancient philosopher, Epicurus, offered a simple cure for panic. He told us not to worry about the gods. They are busy keeping the universe in motion. They have no interest in harming us.

But if we are going to pray, we might pray for wisdom and tranquility. This is what Socrates would have prayed for. In fact, at one point Socrates offered a prayer to Pan himself. He asked the god for integrity of soul. As Socrates put it, “grant me a beautiful soul in which the inner and outer self are united as one.”

A beautiful soul is stable and secure. It is at one with itself. It dwells in the company of truth. It is moderate and self-possessed. And it is resistant to panic.

The philosopher Seneca said the best way to prevent panic is to understand it. You need to understand that when “the habit of blind panic” takes over, the mind runs away with itself.

When we are not prepared for fear and hardship, panic strikes. Seneca explains, “the unprepared are panic-stricken even at the most trifling things.” And when uncontrollable and “witless” panic arrives, things get worse. Seneca’s solution is to adopt a larger point of view that puts life, death, and panic itself in proper perspective.

It is uncertainty that keeps us on edge. The fear that occurs out in the wilderness is like the fear of the dark. We’re not sure what’s lurking out there. That’s why knowledge helps. There is nothing in the dark that is not also there in the light.

It also helps to understand that fear is natural and has a purpose. There is a tightness in the belly and shallow breathing. We scan the environment looking for threats. This is the flight or fight instinct ready to go. If a threat emerges, the body is ready to react.

But this can get out of control, especially when everyone else is on edge. Panic is contagious. We sense the anxiety of our neighbor. If even a minor spark lights the fuse of anxiety, the herd erupts into a frenzied stampede.

This is why solitude is helpful. Peace of mind is easier to find if you keep your distance from the crowd. One easy way to prevent panic is to turn off your television and stay off social media.

But for some people, solitude causes panic. There is the fear of missing out and the depressing dread of loneliness. True solitude is not lonely. It is peaceful and centered, a way of finding yourself at home in the world.

Finally, the philosophers teach that we must understand that death, loss, and injury are common. Tornadoes, earthquakes, and deadly diseases have always existed. They always will. Something will eventually kill each of us. No one gets out of this life alive.

When we come to terms with our own mortality, panic gives way to acceptance. To live well is not to fearfully cling to life. This moment will not last long. So why waste it on worry? Life is not measured in length but in depth. The shallow panting of panic prevents us from breathing deeply and living well.