Covid-19 has transformed Thanksgiving. This year we should shelter within our bubbles and stay close to home. Rather than complaining about a downsized holiday, let’s use this as an opportunity to rediscover the wisdom of living modestly and being thankful.

Ancient wisdom celebrates gratitude and simplicity. Ancient sages teach us to be grateful for simple things and to celebrate abundance without extravagance.

Thanksgiving has strayed far from this idea. Rather than a time to count your blessings and give thanks, it became an orgy of over-indulgence. The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade is a department store advertising gimmick. The Black Friday frenzy is far removed from gratitude. Good riddance to these extravagances.

The Puritans of New England would be appalled that this festival of gluttony and greed commemorated their colonial adventure. The Puritans connected thanksgiving with repentance and purification. Instead of feasting, early Americans typically linked the ritual of giving thanks to fasting. Thomas Jefferson called for” public days of fasting and thanksgiving” when he was governor of Virginia. During the civil war, Abraham Lincoln called for several days of “fasting and thanksgiving.” In 1863, when Lincoln declared a national day of thanksgiving, he called for a day of prayer and “humble penitence.”

This may go too far for those of us with a more secular orientation. But there is wisdom in humility and abstinence. You don’t have to be a Puritan to understand this. Abstinence clarifies values. Fasting heightens appreciation for simple things. A thanksgiving feast that breaks a fast should consist of modest fare, eaten mindfully.

Mindfulness, gratitude, and abstinence are linked in most of the world’s traditions. Muslims practice something like this during Ramadan. The Buddha fasted and meditated on the way to enlightenment. Ancient Taoist texts speak of “fasting of the mind” giving rise to the freedom of emptiness.

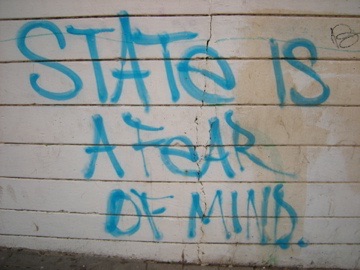

This is not as far out and mystical as it sounds. Mindful self-restraint quiets envy and desire. The consuming self is like a vacuum. It sucks things in: food, pleasure, and possessions. But all of this frantic sucking produces anxiety, fear, greed, and envy.

The mindful self stops sucking. It becomes less focused on its own emptiness and more aware of its secret abundance. The Greek sage Epicurus said that we already possess all that we need in abundance. But we are confused. We mistake wealth for happiness. And we allow greed to make us ungrateful.

When we discover self-sufficient abundance, it overflows. It then becomes easier to give—and to give thanks. The consuming self is a sucker and a taker. The grateful self is content with what it has. And in its contentment, it discovers compassion.

The ancient Greeks advise us to gratefully accept what fate gives us. Seneca recommended an occasional fast as a reminder to be thankful. This trains the spirit to be content no matter what fate sends our way. Stoic serenity does not depend on money or good fortune. Rather, it is built upon simplicity and gratitude.

Seneca expressed these ideas in a letter criticizing the Saturnalia, the Roman equivalent of our holiday season. He complained that preparations for the annual orgy went on all year. And he noted that the season culminated in drunkenness and vomiting. Seneca said it is wise to avoid all of that and to learn to “celebrate without extravagance.”

The pandemic can help us re-learn this ancient lesson. The usual extravagances have been cancelled. And we are forced to abstain. Rather than complain, let’s rediscover the wisdom of simplicity and gratitude.