Selfie culture and mindfulness

Fresno Bee, January 8, 2016

- Examining the tyranny of the selfie

- Selfies are signs of narcissism, exhibitionism

- Mindful absorption is a key to happiness

Selfies are everywhere. Celebrities snap them. Popes and presidents have taken them. And dumb criminals record their own crimes.

Hillary Clinton recently lamented what she called the “tyranny of the selfie.” Voters want selfies with candidates – and don’t really care much about the issues. Somehow we think that if we get an awkward picture of ourselves, we’ve accomplished something.

Selfies are not without risk. Dozens of people have been killed or injured trying to get the perfect selfie. A student fell to her death recently in the Philippines while attempting a dramatic selfie from a rooftop.

In order to take a selfie, you have to turn your back on the action. This is obviously dangerous. It is also symbolic. The selfie combines narcissism, voyeurism and exhibitionism with disengagement and distraction.

Our narcissism is obvious. We want badly composed close-ups taken at arm’s length. And we send them out to the world.

Our culture encourages us to believe that if it is not recorded, it is not valuable. We are voyeurs, obsessively watching other people do things – on TV and online. We are also exhibitionists, shamelessly displaying ourselves to the world.

Very little remains private in the age of voyeurism and exhibitionism. Sexting has democratized pornography. It is quite common for people – including teenagers and an occasional politician – to exchange naked photos.

Even apart from the naughty stuff, there is something awry in a culture where everything is done with and for the camera. One problem is that we often think that if we’ve taken a picture, we’ve done our part.

Students in my classes no longer take notes. Instead they take pictures of what is projected on the overhead. But taking a picture is no substitute for taking notes – or for thinking.

Here is a New Year’s resolution: to remain thoughtfully focused on the moment without fumbling with our phones.

Human beings are happiest when we are immersed in activity. A happy life involves mindful engagement with the world. Folks who are fully engrossed in the world often forget to take a picture of it.

Sure, the moment will pass. If you don’t take a picture, you might forget it. But the recipe for happiness it to let this moment blaze in all its glory, then move on and find joy in the next. The happiest people lead busy lives, which rarely leaves time to look back at their own selfies.

Happiness is not captured in a selfie and exhibited online. Happiness is an ongoing activity. Happiness is not something we are; it is something we do. Happiness does not come from watching others or ourselves; it comes from doing things.

Happiness, like love and learning, requires engaged activity. If you want to be happy, get busy doing good things. If you want to learn something or love someone, be focused, engrossed and aware.

Some traditions advise that enlightenment comes from learning to do nothing. The world’s contemplative traditions maintain that serenity is found in silent stillness. Meditation calms the mind and helps us focus.

Attentive absorption in the present is a cure for the distracted frenzy of our selfie-snapping world. To be mindfully engaged with what we do and those we do it with, we need to look at them directly instead of mugging for the camera.

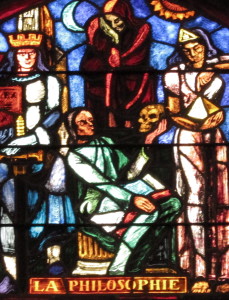

Meditation and other contemplative practices aim to cure us of our obsessive focus on ourselves. It is difficult to image a Zen master picking up a phone in order to record nirvana. It is also difficult to imagine Jesus posing for a selfie with his disciples.

Enlightenment, love and ethics are antithetical to the narcissism and disengagement of our age. Ethical engagement is not undertaken with an eye to the camera. And a picture is often worth much less than careful attention to the moment and those we love.

We take pictures of ourselves doing things in order to prove to others (and to ourselves, I suppose) that we are having fun. But turning your back on the action to prove that it’s fun breaks the spell of the moment.

Here is some advice from the sages: Be mindful in your deeds. Learn from stillness. Love without reserve. And if you must take a selfie, watch your step.