Most of society is pushing for vaccine mandates. But a small minority is opting out on religious grounds. That’s their right under the First Amendment. If your deeply held beliefs prevent you from getting a vaccine, you can get a religious exemption.

In the United States, the First Amendment allows for “free exercise” of religious belief and other freedoms. These principles are connected to the right to have an abortion, the right to refuse to serve in the military, the right of gay and lesbian people to marry, and the right to refuse to salute the flag.

We value religious liberty in this country and freedom of conscience. This does not mean that religious people can sneeze germs wherever they want. Those with religious exemptions still need to wear masks, to self-quarantine when ill, and to undergo routine testing. But so far, no one is going to force you to get a shot, if you are conscientiously opposed to the idea.

There are complexities here involving what counts as a religious exemption. Some vaccine denial is not of the “conscientious” variety. Instead, it is based on crackpot conspiracy theories. But then again, one person’s deepest religious beliefs may be viewed by another as a crackpot conspiracy theory. That’s why we ought to tread lightly.

Official policies regarding religious exemption show the difficulty. In the California State University policy, for example, it says that a religious exemption can be granted either for “sincerely held religious belief” connected to “traditionally recognized religion” or for sincere beliefs that are “comparable to that of traditionally recognized religions.”

This means that agnostics and atheists can be granted “religious” exemptions. But would a devoted QAnon believer also qualify? It is difficult to decide what counts as a sincerely held belief worthy of exemption.

Religious exemptions in the United States have evolved through litigation. Originally, exemptions from military service were granted only for members of historic peace churches. Over time, the interpretation of what counts as grounds for conscientious objector status expanded along with religious diversity and the growth of non-religion.

The question of what counts as a religion is vexing, especially in the U.S., where new religions grow and prosper. The U.S. has given us Mormonism, Seventh Day Adventists, Christian Science, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and the Nation of Islam — along with Scientology and the Church of Satan.

When is a group of like-minded folks really a “religion”? And when are your beliefs worthy of accommodation? In the U.S., we are permissive in this regard. If you publicly testify to the sincerity of your belief, we’ll accept that for the most part.

A data dump from California State University Chico provides a bit of insight about how this might play out. There are ethical concerns about the breach of privacy that occurred when Chico State’s data was revealed. But the published accounts show the kind of language used by students who were granted exemptions. One claimed, for example, to believe in “natural healing through God’s divine power.”

It would be wrong to force someone with that kind of belief to violate their conscience and take the vaccine. In the same way, it would be wrong to force a committed pacifist to take up arms or a believer opposed to state-idolatry to salute the flag.

Some people will lie about this. But how can we know? It is very difficult — if not impossible — to judge the sincerity of another person’s profession of faith. If someone publicly declares their belief in something, we take them at their word, until evidence is provided that shows they are lying. Of course, if you lie on your application, that’s fraud, and this may have legal repercussions.

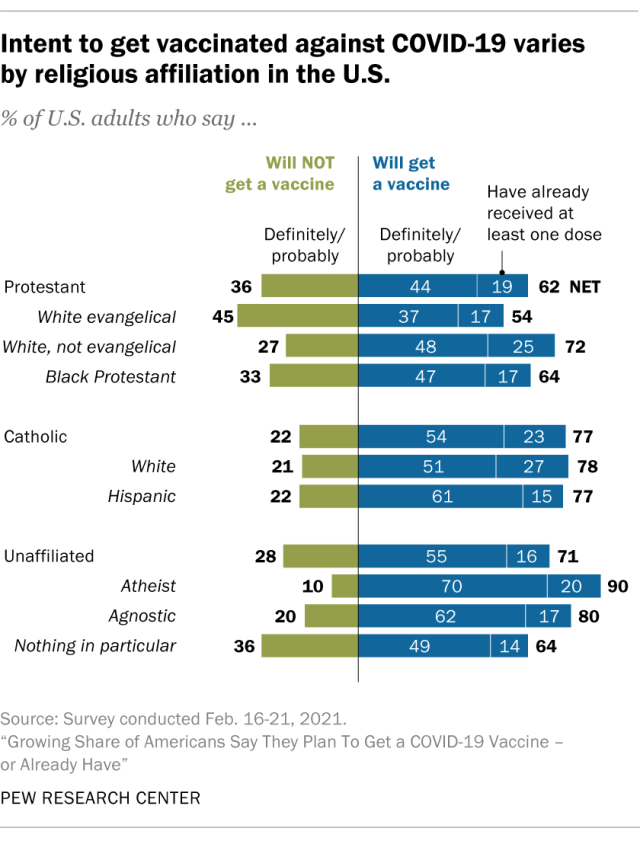

It is likely that the number of people asking for religious exemptions will be small. There are few people whose religious beliefs prevent them from saluting the flag or from carrying arms in defense of the country. There are likely also few people whose faith prevents them from using modern medicine.

These religious exemptions provide a great opportunity to educate ourselves about the First Amendment and the complexity of religion. It also provides each of us with a chance to think about what we sincerely believe.