Self-care is a common theme for 2021. One wellness website said: “focus on yourself this New Year’s Eve” and “indulge in these self-care strategies as you enter 2021.” The article recommended “allowing yourself to indulge in a night of luxurious me-time.”

This is not a bad idea. A little self-care is fine from time to time. But self-indulgence is occasional. It is not a way of life. We need something larger and less transitory. Self-care should become self-cultivation.

The self is not an infant we care for or a set of appetites to be indulged. The self is a dynamic system that seeks fruitful activity. The adult self is a growing and changing, goal-oriented being. The self thrives when it is challenged; it prospers when it produces lasting goods such as love, art, science, virtue, and wisdom.

The pampering indulgence of self-care is aimed at stressed out people. Self-care is an antidote to the rat race and a response to the tragedies and suffering of 2020. But “me-time” should not climax in onanistic withdrawal. 2021 will require the active intelligence of an engaged self.

There is some wisdom in self-care. The self-care movement often affirms modesty and mindfulness. This affirmation of simple pleasure is useful for those who are wound up tight by our cranky, competitive culture. It is OK to unwind on occasion. Drink some wine. Soak in a tub. Take it easy.

Sometimes the self-care movement offers clichéd common sense about hygiene and mindfulness. Yes, we should drink more water, be present, and take walks in nature. But this often becomes sappy, self-indulgent pampering—an apology for sleeping late or over-eating. And self-care is often merely a marketing ploy for spas, lotions, and chocolate.

The self-care movement is quite broad. On the one hand, it includes the discipline of yoga. As one yoga website puts it, “Yoga is a great form of self-care.” On the other hand, self-care is about… well, something else you do with your hand. An article in The Oprah Magazine celebrates masturbation as part of a “self-care routine.” The author reports that some evenings she even cares for herself twice!

There is nothing wrong with pleasure. But moderation is essential. And pleasure is not an end in itself. Happiness and morality often require us to forego pleasure. Work, discipline, and focus are essential for the self to thrive. Stress and anxiety are essential parts of a creative and ambitious life. When other people are suffering, self-care is selfish. Justice and compassion impel us beyond self-care toward care for others.

This discussion can be traced back to the conflict between Epicureans, Stoics, and Christians. Epicurus suggested we should live modestly, avoid controversy, and enjoy simple pleasures. The Stoics rejected this. They emphasized strenuous duty, while claiming that pleasure makes us soft. Christians also rejected Epicureanism, focused as they were on suffering, death, and resurrection. Epicurean self-care is too sensual for Stoics and too secular for Christians.

Ideally, we would weave these ideas together by connecting self-care with self-cultivation.

Care is rooted in a kind of worry. A care-free person has no worries. When we care for something, we worry about it. The problem of self-care is that it is a kind of worrying about the self. It can be onanistic and self-absorbed.

Cultivation is much more affirmative and dynamic. When we cultivate something, we grow it. Cultivation is related to “culture.” Culture is a dynamic process that is the result of labor, interaction, and imagination.

Human beings are not only focused on pleasure and relaxation. We are also concerned with love, justice, courage, compassion, knowledge, art, and wisdom. When we are absorbed in fulfilling activities, the self fades away. The self-oriented path of indulgence is limited in comparison with the self-less activity of inspiration, insight, and interconnection.

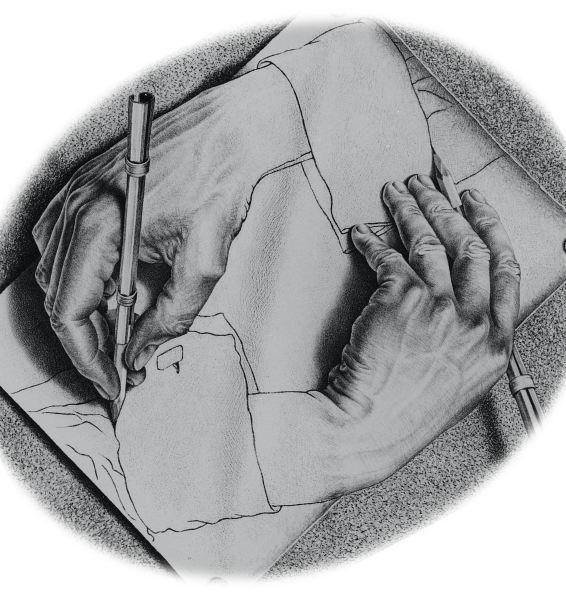

So here is what I propose for the new year. Instead of retreating to the bathtub, let’s put our hands to work. Learn. Teach. Create. Make music. Do science. Love your neighbor. Fight for justice. Pursue wisdom. These are the goods of a fully human life. The challenge of 2021—and of life in general—is to cultivate a self that loses itself in inspired and engaged activity.