Labor Day is a good time to reflect on ethics and the economy. Honest, hard-working people should be able to earn enough money to live decent lives. There is something corrupt about wealth that is divorced from work. And rich people don’t deserve more social and political power than the working class.

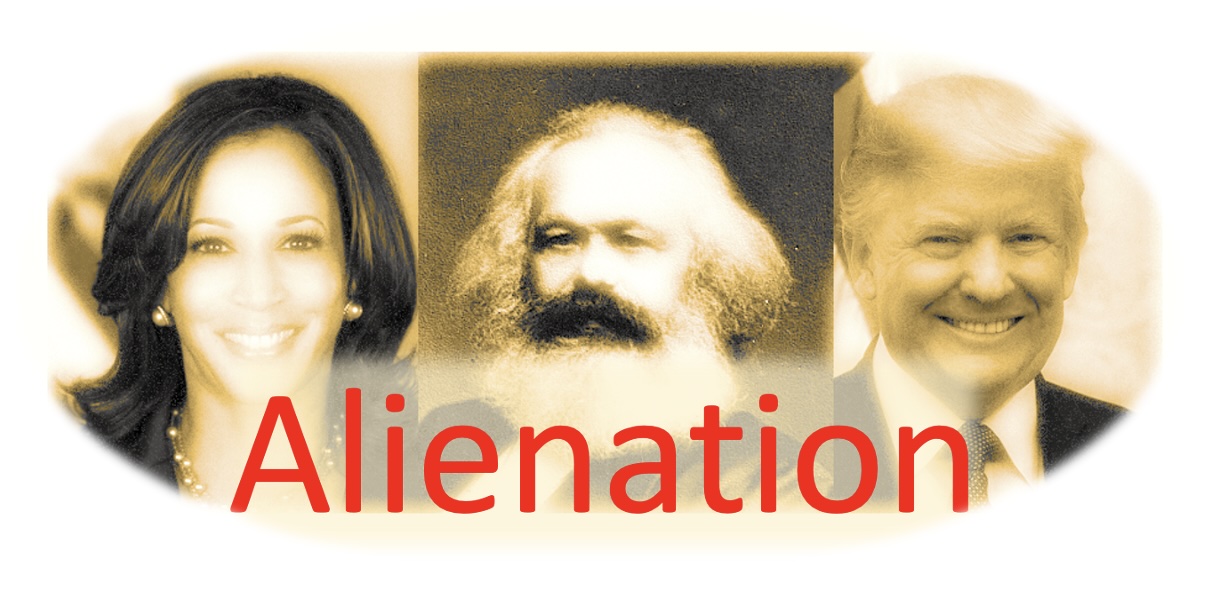

These common sense ideas might sound socialist. Unfortunately, the mere mention of the “s-word” or Karl Marx can provoke outrage. Socialism and Marxism are anathema to many Americans, having become terms of insult in our culture wars. And, recently, Donald Trump has repeatedly accused Kamala Harris of being a Marxist — he calls her “comrade Kamala.” “We’re not ready for a communist president, okay?” Trump recently said of Harris.

This is ridiculous. Harris is a mainstream liberal proposing moderate help for consumers on housing, health care and food costs — proposals that are popular among voters. Harris even seems to agree with Trump about eliminating taxes on tips.

Harris is not proposing a communist revolution that would abolish capitalism or centralize production in the hands of the proletariat. And yet she is absurdly accused of being a Marxist.

The accusation is occasionally linked to an insinuation about her estranged father, Donald J. Harris, a former Stanford economics professor who did, in fact, publish work on Marx.

But this kind of ad hominem and innuendo is silly. It’s as bad as the argument made against Trump regarding the fact that he inherited his wealth from his racist father. What matters is a candidate’s current views and policy proposals — not something dredged up out of their biography, over which they have no control.

At any rate, one wishes there were a candidate who addressed alienation and inequality head on. This would ring a bell for many Americans who feel that the economy is rigged against them, and who are disenchanted with the whole social and political system.

Notably, alienation is a Marxist idea. A young Marx coined the term “alienated labor” in the 1840s to describe how labor produces surplus profit that goes into the capitalist’s pocket. Marx says this empowers the wealthy, while impoverishing the worker.

Things have changed for the better in the past centuries. Economic regulations prevent the kind of exploitation and miserable conditions that afflicted workers in the 19th century. But the general concept of alienation remains useful: Drudgery, poverty and inequality remain problems, and people are disillusioned with politics and the economy.

The Harris Poll’s “alienation index” has tracked this for decades. A majority of Americans report a deep sense of alienation when asked whether elites care about them or whether the rich get richer while the poor get poorer.

Hard-working people often can’t afford adequate housing or other basic goods. The working poor lead precarious lives, earning low wages doing unpleasant and dangerous jobs. They find themselves in debt, unable to get ahead or even imagine retirement. An accident or health crisis can throw them into homelessness.

Meanwhile, some lucky stiffs inherit wealth or otherwise hit the jackpot. The truly wealthy put their money to work in the stock market, earning millions without breaking a sweat. The wealthy are able to pull strings and gain access to a world of luxury and power that the poor can only imagine.

This difference of life prospects and social power produces instability and resentment. Different classes of people inhabit different economic and political realities. When social classes are estranged from each other, they grow suspicious. The wealthy pull away from the masses, retreating into gated communities and luxurious clubhouses. And those on the bottom are alienated from the system itself. They give up on voting or caring, since they think the whole thing is rigged by the rich at the expense of the poor.

To name alienation is to echo Marx. This is not to say that Marx was right about everything or that a communist revolution is needed, but alienation remains a significant social problem. Too many workers live precariously. The average Joe resents the fat cats in first class, and lots of people distrust the system. These are profound and perennial issues. Our leaders need to address these problems. And they might even learn something from reading Marx.

Read more at: https://www.fresnobee.com/opinion/readers-opinion/article291660565.html#storylink=cpy