Tranquility is often viewed as the goal of spiritual training. But serenity is not the only thing that matters in life. Conflict is productive. Struggle is exciting. And anxiety is the spice of life.

Arthur Brooks wrote an essay recently pointing out that suffering, unhappiness, and anxiety are unavoidable experiences. He was responding to the apparent growth of mental health disorders, including a recent increase in depression and anxiety. This is alarming. And I don’t intend to minimize the problem.

But there is some wisdom to be learned from the world’s wisdom traditions, and from how we imagine a good life. Here’s the point: life is difficult. The key to living well is not to find a peace place and to avoid conflict and struggle. Rather, the goal is to manage conflict and create a harmonious whole.

Dialing in the virtues

In his essay, Brooks asks us to see that our emotions are not regulated by simple on-off switches. Rather, they are like dials. They can be adjusted upward or downward. The goal of living well is to adjust these dials and to balance our emotions with one another.

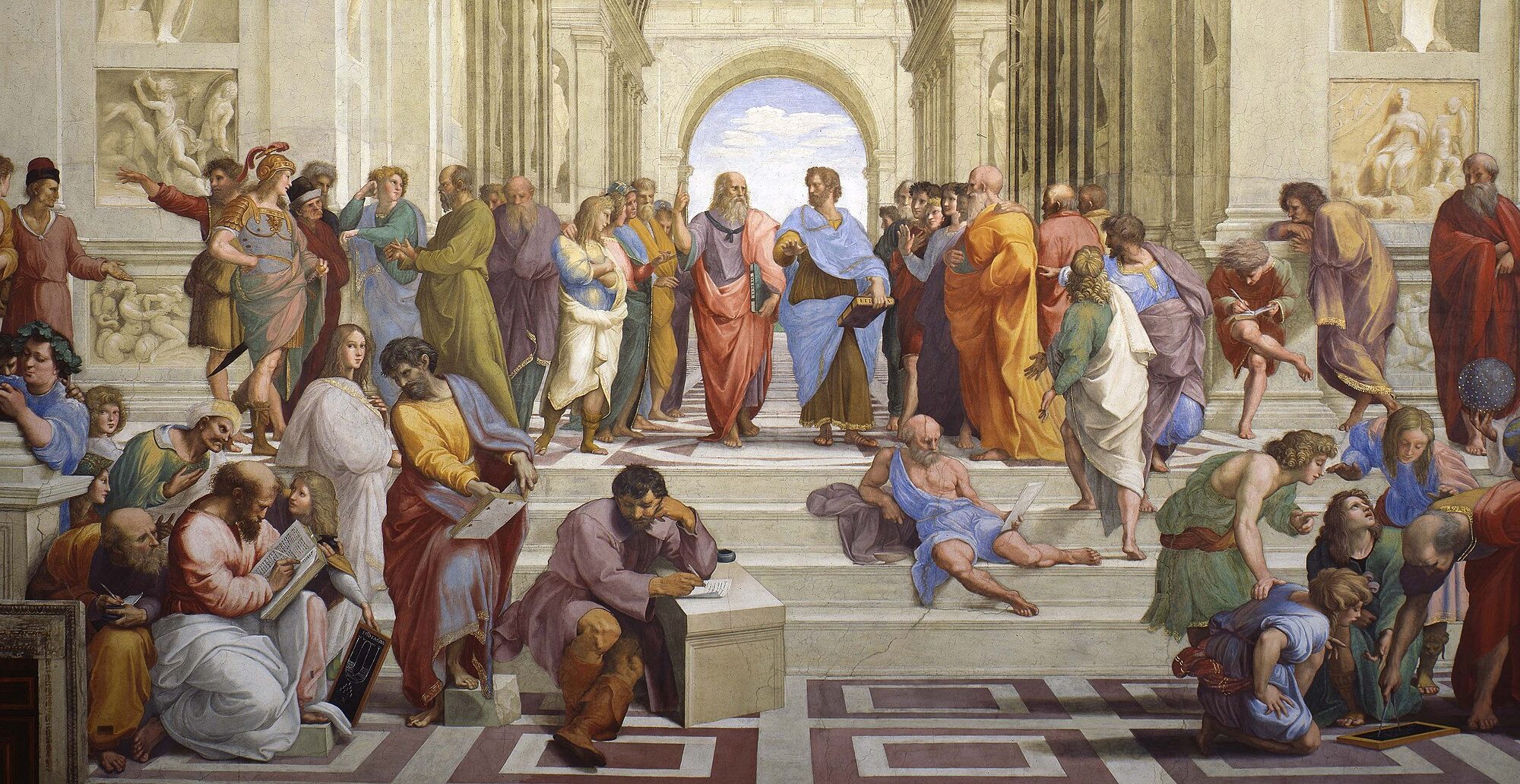

I would add that this is also true of the virtues. The four Platonic virtues—justice, courage, moderation, and wisdom—are not binary switches. Rather, they are like dials that are adjusted in relation to the world. The virtues must also be balanced with each other. Aristotle reminds us that the key to happiness is to find the right amount of a virtue, at the right time, and in the right way.

A familiar example involves courage. Would we say that a criminal is couragous when he robs a bank? Not really. Courage does not occur in isolation. It must be connected to the other virtues. Sometimes courage needs to be dialed up: say when you need to defend what’s good and what’s true. But at other times, it needs to be dialed down: when you are selfish, resentful, and mean.

In the Greek tradition, wisdom helps us adjust the dials. But there is no recipe or rule that helps us figure out how best to adjust these dials. This is more art than science, which leads us to a culinary and aesthetic metaphor.

Cooking up wisdom

The challenge—and the fun—of adjusting our dials is obvious for anyone who is familiar with music or with cooking. Consider the process of cooking, eating, and drinking. The pleasures of dining involve contrasts and balance. Red wine is good with pungent cheeses. Hot chilis pair well with lime and sweets. A delicious meal involves the interplay of lots of flavors, textures, and smells. And these unfold over time—from the appetizer to desert.

Life is like a complex meal. There are spicy parts, and mellow times, salt and vinegar, sweetness and light. The key is balance. But also play and innovation.

So too with music. A single note is boring, as is a simple rhythm. Symphonic music and jazz demonstrate the joy and beauty of complex harmonizing. The bass line runs in contrast to the melody. The chords change. Those changes include dissonance, odd little grace notes, and tonic resolution. There are slow movements, staccato outbursts, and groovy backbeats. Sometimes there is a key change. Other times the bridge introduces a whole new concept.

What if we viewed our lives as musical compositions? We would strive for a complex balance of fast and slow, resolution and dissonance. Sometimes life is marked by sad blue notes. Other times it rings like a bold major chord. The goal is to weave it all together with a sense of harmony.

Harmony v. tranquility

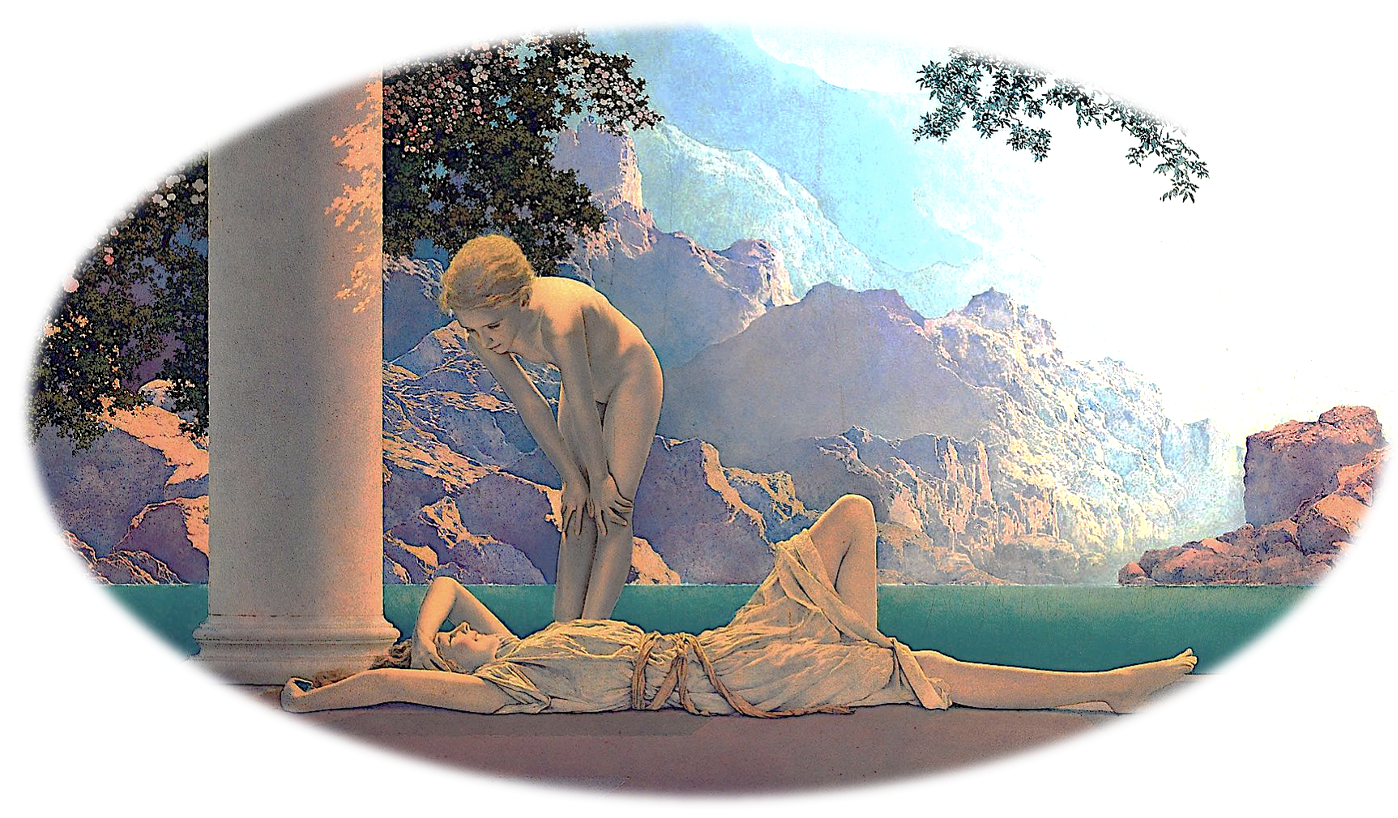

The goal of life is not, then, to rest quietly, serenely, and in peace. Some spiritual traditions do seem to point in that direction. We might imagine a monk alone on a mountaintop, sitting in quiet contemplation.

But that vision is other-worldly, and inhuman. It takes us to a summit far removed from the joys and the sorrows, the anxieties and loves of real human life. A life well-lived includes fear, sorrow, and grief. Those are necessarily components of a life that includes ambition, love, and compassion. The key is to dial these things up in the right way and in the right amounts.

If you love others and yourself, there will be anxiety and sadness. Love exposes us. When others hurt, you hurt as well. This is appropriate, and real. If you love yourself, there will also be anxiety. Our goals and ambitions matter. It is good to feel proud of what you’ve achieved and who you are. It is also right to feel resentful when the world turns against you. And it is appropriate to feel sad, when the world disappoints.

The challenge of a life well-lived is to weave anxiety and sadness into a harmonious whole. Life includes a variety of ingredients: joy and worry, sorrow and pride, love and grief. We don’t control everything that life gives us. But we can adjust the dials. Every life will include substantial amounts of bitter seasoning. The goal is not to stop eating, or to live in quiet serenity. Rather, we ought to aim to create a symphony of the sweet and the spicy.