Fresno Bee, March 9, 2025

How Donald Trump and Elon Musk inspire passions feared by America’s Founding Fathers

American politics has become deeply erotic. Often, this manifests as love — as when Elon Musk recently tweeted, “I love Trump, as much as a straight man can love another man.” In his recent address to Congress, President Donald Trump said: “People love our country again, it is very simple.” He extolled the “faith, love and spirit” of the American people, who “will never let anything happen to our beloved country.”

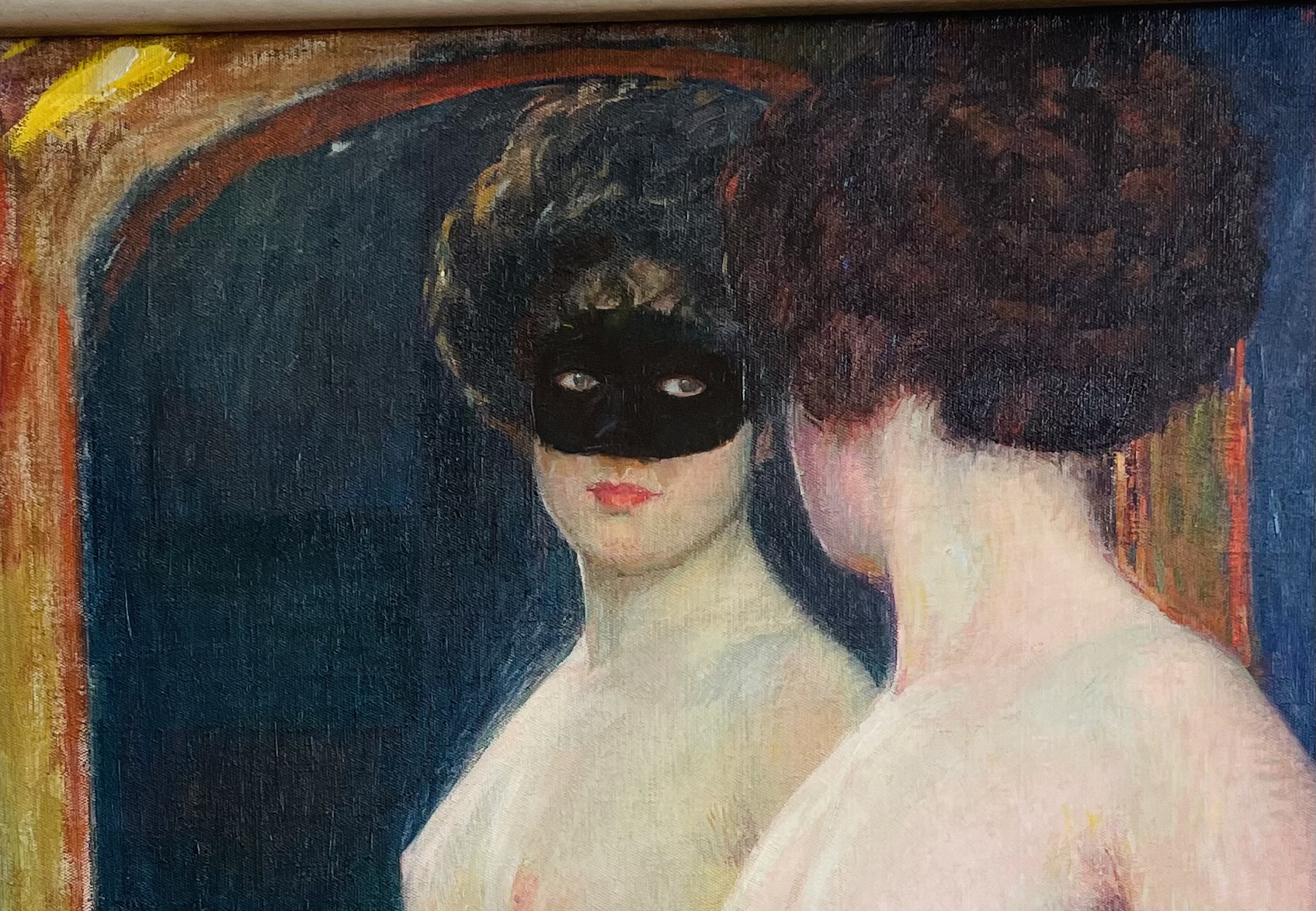

To say that Trump is an erotic leader does not mean he is “sexy.” Rather, the point is that he provokes. Trump inflames the emotions — whether you love him or hate him. He is the kind of person about whom it is nearly impossible to remain indifferent. He arouses rather than enlightens.

The erotic element shows up in various ways. Fealty and devotion of the Muskian sort are obviously forms of love. Nepotism and cronyism are erotic ways of distributing power to faithful friends and family members. In such arrangements, it does not matter whether things are fair or reasonable, nor does it matter whether people are good. Rather, what matters is love and connection.

Trump is making American politics a game of seduction and power — a spectacle driven by passion. Part of this is public performance. As Trump was berating Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy the other day, he said, “This is going to be great television.” The play of passion is enthralling and compelling: you can’t look away.

In a comment on the Zelenskyy episode, Canadian novelist Stephen Marche suggested we are witnessing “rule by performers,” and what he calls “histriocracy,” the rule of the “histrionic,” — the melodramatic, theatrical or emotional. Indeed, Trump is a master of spectacles, and he knows how to keep us watching.

The erotic art of arousal can be useful in business and in politics. But it is quite different from a more sober-minded or rational approach to the world.

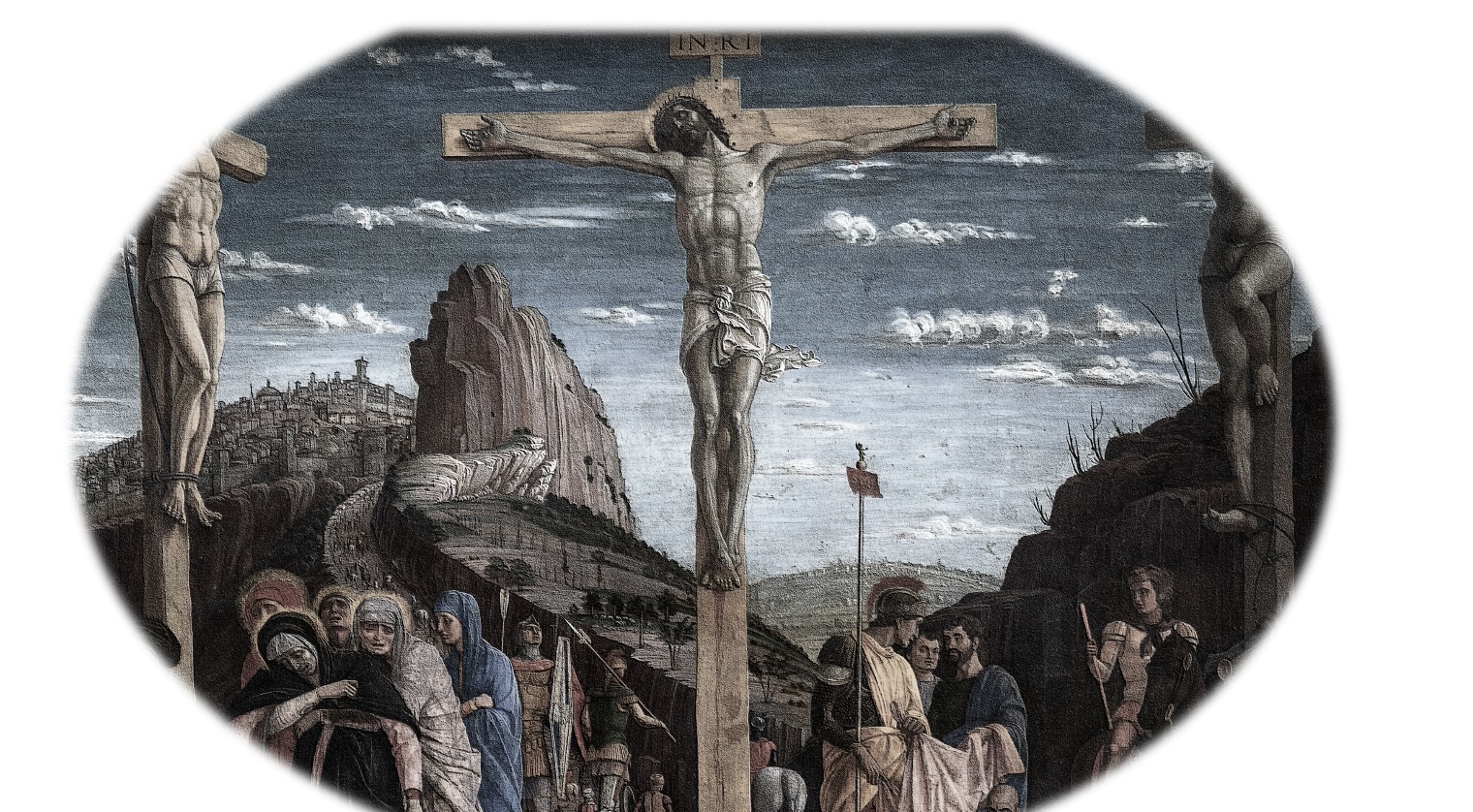

The distinction between the erotic and the rational is as old as Plato, who worried that unbridled eros (sexual love or desire) would destroy a good city, and that passion would undermine justice. He warned that when eros rules a city (or a soul), it is like being drunk or mad. The rule of the erotic leads to lawlessness, frenzy and tyranny. Plato hoped rationality could control the passions, but he knew that eros was a powerful force.

Sober-minded folks view political discourse as an earnest discussion of justice, virtue and truth. Rational politics is sincere, honest and moderate. In the Platonic government, careful thinkers would deliberate using logical arguments that rest upon a bedrock of first principles and unassailable truths.

Passionate politics is different. It values histrionic performances that elicit emotional responses. Here, the participants seduce and cajole with the goal of achieving popular acclaim — which is, after all, a kind of love. The erotic approach rejects sedate sincerity in favor of impassioned public displays of power and affection. Erotic politics is more interested in glory than in goodness, and it encourages inspiring fantasy rather than dull deliberation.

Political eros is chaotic and unreasonable. Sometimes, it even becomes vulgar and obscene. The risk that passion will become excessive is part of what makes it exciting and fun. That’s why sober-minded rationalists don’t understand its allure and worry that the excitement of eros will lead to dangerous excess.

John Adams once warned about the “overbearing popularity” of “great men.” He said, “Ambition is one of the more ungovernable passions of the human heart. The love of power is insatiable and uncontrollable.”

Adams and the other Founding Fathers created a system of checks and balances to restrain the erotic element. Rationalists like Adams think that laws should rule, rather than love. They view passionate personalities as dangerous, and in need of restraint.

Eroticism sees such sober rationalism as boring and shallow. Typically, devoted lovers remain enamored of their charismatic champion — despite their flaws and lawlessness — and because of his passion. Indeed, those flaws may make this figure more beloved.

In erotic politics, people are wedded to the person of the leader, warts and all. This astounds sober-minded defenders of virtue and the rule of law. But in erotic politics, it makes perfect sense to remain devoted to the beloved, since love is love, no matter what.

Read more at: https://www.fresnobee.com/opinion/readers-opinion/article301565739.html#storylink=cpy